Why mathematicians should care about Large Language Models

This post is to review some remarkable observations by Microsoft and DeepMind researchers regarding the apparent ability of Large Language Models (LLMs) to solve mathematical problems. I believe mathematicians should sit up and take notice of these examples: we need at the very least to understand them - and to ask what they might mean for the future.

1. A surprising example

Let’s start with a teaser - actually a version of a question from the 2022 International Mathematics Olympiad:

Suppose $g$ is a continuous smooth function such that for every $x > 0$, there is one and only one $y > 0$ such that $g(x) + g(y) ≤ 2xy$. Can you prove that $g(x) = x^2$?

If you haven’t seen this before, I invite you to give it a little thought before proceeding.

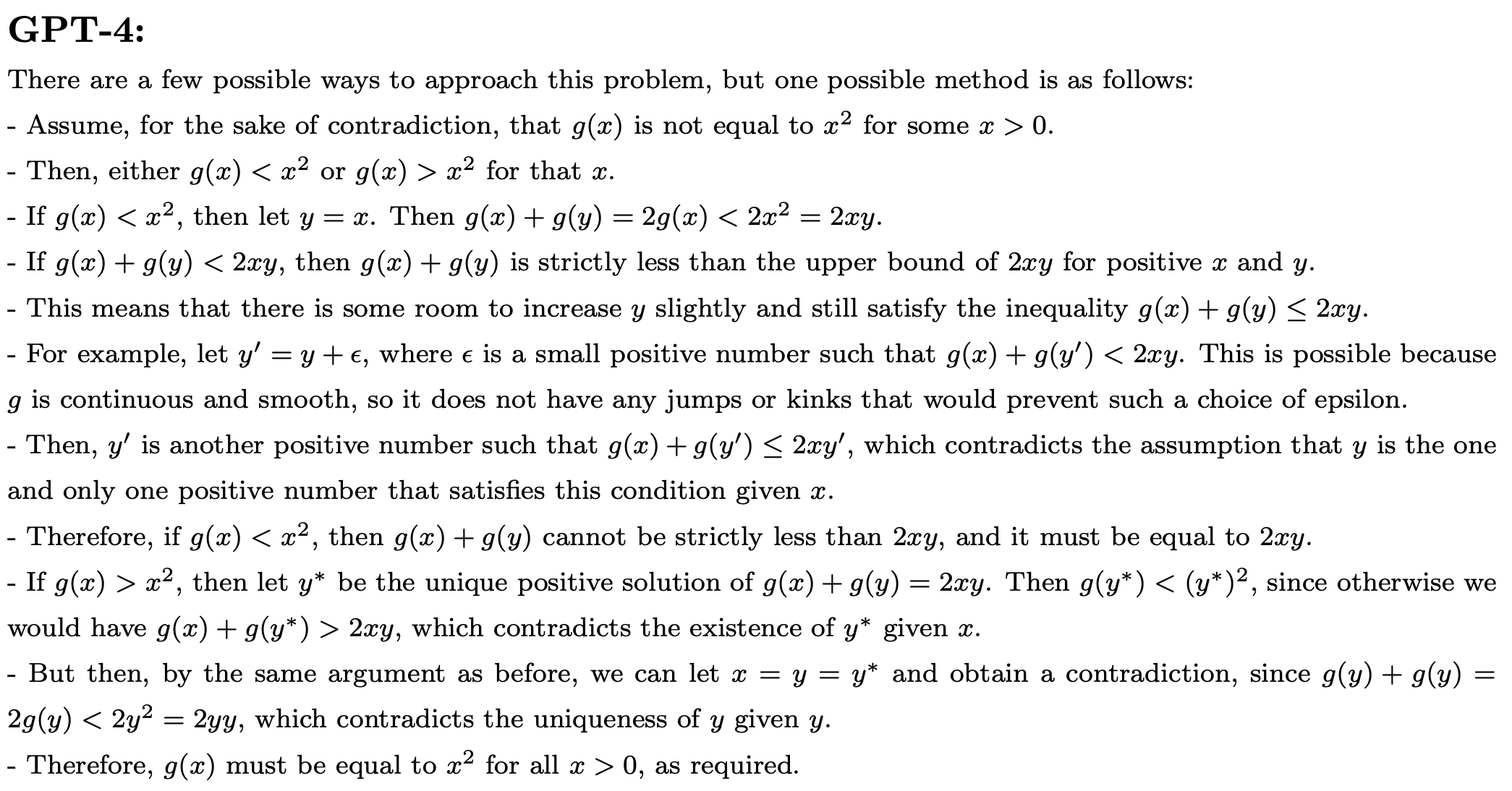

OK, thought about it enough? This is an example cited in a study of GPT-4 last year by Microsoft researchers [1 section 4.4]. It is put to GPT-4 as a prompt - here is the model’s response:

What do we see? In principle, the chatbot is based on a sophisticated auto-complete - probabilistic next-word selection to construct a text response. Yet the result is some coherent reasoning which correctly solves the problem presented. Moreover, it’s not a standard problem: it would be surprising and challenging to most students.

Conceivably, this same problem occured somewhere in the training corpus used to build the language model and GPT-4 is simply regurgitating a known answer - I’ll return to this possibility below. Yet this example is just one of many similarly jaw-dropping interactions with GPT-4 cited in [1]. Could they all have been in the training data?

What is going on here?

2. It’s Reinforcement Learning, stupid!

A base LLM is a sequence-to-sequence (transformer) model built on a huge amount of text - typically 10s of billions of words - trawled from the Internet. It is built to model next-word probabilities based on long stretches of text. In this sense, it can be described as a very powerful ‘autocomplete’ capability.

This does not tell the whole story, however. A base LLM alone would not be able to produce the kind of performance illustrated above. In a user-facing system such as GPT-4 there is much more going on, as introduced by OpenAI in [2] and explained in the excellent article by Aerin Kim [3].

The magic that turns a base LLM into a high-performing, all-knowing chatbot is referred to as Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). In my view, this rather modest terminology doesn’t do justice to the cleverness of the design - though it does reveal that the most important ‘secret sauce’ is human input - lots of it, of high quality and meticulously managed.

Briefly, the design consists to three machine learnt models:

- SFT model. This stands for Supervised Fine Tuning, and is a further tuning of the parameters of the base LLM using ‘instruction data’ - which I’ll describe in just a moment.

- Reward model. This is a second model which assigns a score to any pair (prompt, response).

- Policy model. This is a reinforcement-learnt model, which, given a text sequence, chooses a next-word (an ‘action’) with the goal of maximising the end-reward (as computed by the reward model).

Let’s think about that for a moment. When GPT-4 responds to a user prompt, it is not simply auto-completing using next-word probabilities. What it is doing is more akin to game-playing: at each point in the game it has constructed a sequence of text (the current ‘state’); it is offered a choice of actions (the next word) based on probabilities given by the SFT model; it has to choose one of these actions in order to maximise the (future) reward of the final output.

The success of the system comes from having, at each step, the best actions to choose from (thanks to the base LLM and the quality of the instruction data underlying the SFT model) and a reward signal (from 2) that accurately represents the expectations and needs of a user.

The instruction data used to train the SFT model consists of human curated pairs (prompt, response). The reward model, likewise, is trained on significant human input. For this, the training data consists of a large set of prompts (independent of those used for the SFT!), and selections of responses are ranked by human labellers.

According to the discussion in [2,3], this human-generated input is not cheap, crowd-sourced data but follows detailed guidelines and is carefully choreographed. The performance of the system is critically dependent on the quality of this data and not on the power of the LLM alone.

Back to mathematics. Examples like the one above suggest that LLMs can actually ‘do’ maths. What this is based on is models that are in effect compressions of data: of vast amounts of Internet data in the base LLM, but also of large amounts of human-curated data in the SFT and reward models.

The question is, can the LLM do maths that it hasn’t seen before? Had the Olympiad solution at the top of this post been seen on the Internet, so that it was already present in the base LLM? Or could it have occured somewhere in the instruction data?

3. Can AI really discover new mathematics?

In the recent paper [4], researchers at DeepMind found a brilliant way to test the general claim that one can indeed find completely new solutions to mathematical problems by consulting a LLM. (See also their blog post [5].)

Namely, suppose we pick a problem for which progress can be directly evaluated for quality, and which is sufficiently well studied that the state-of-the-art is well established. Then, if we improve on that state-of-the-art using a LLM, we will have compelling evidence that the LLM has found novel mathematics.

In [4] the authors pick the cap set and bin packing problems to study. Bin packing - that is, fitting a collection of variable-sized objects into the smallest number of fixed-sized bins - is well known and ubiquitous in computer science for tasks such as resource allocation. The methods of [4] - which I’ll explain in a moment - are applied to some standard benchmark data sets for bin packing, and in all cases beat previous known methods.

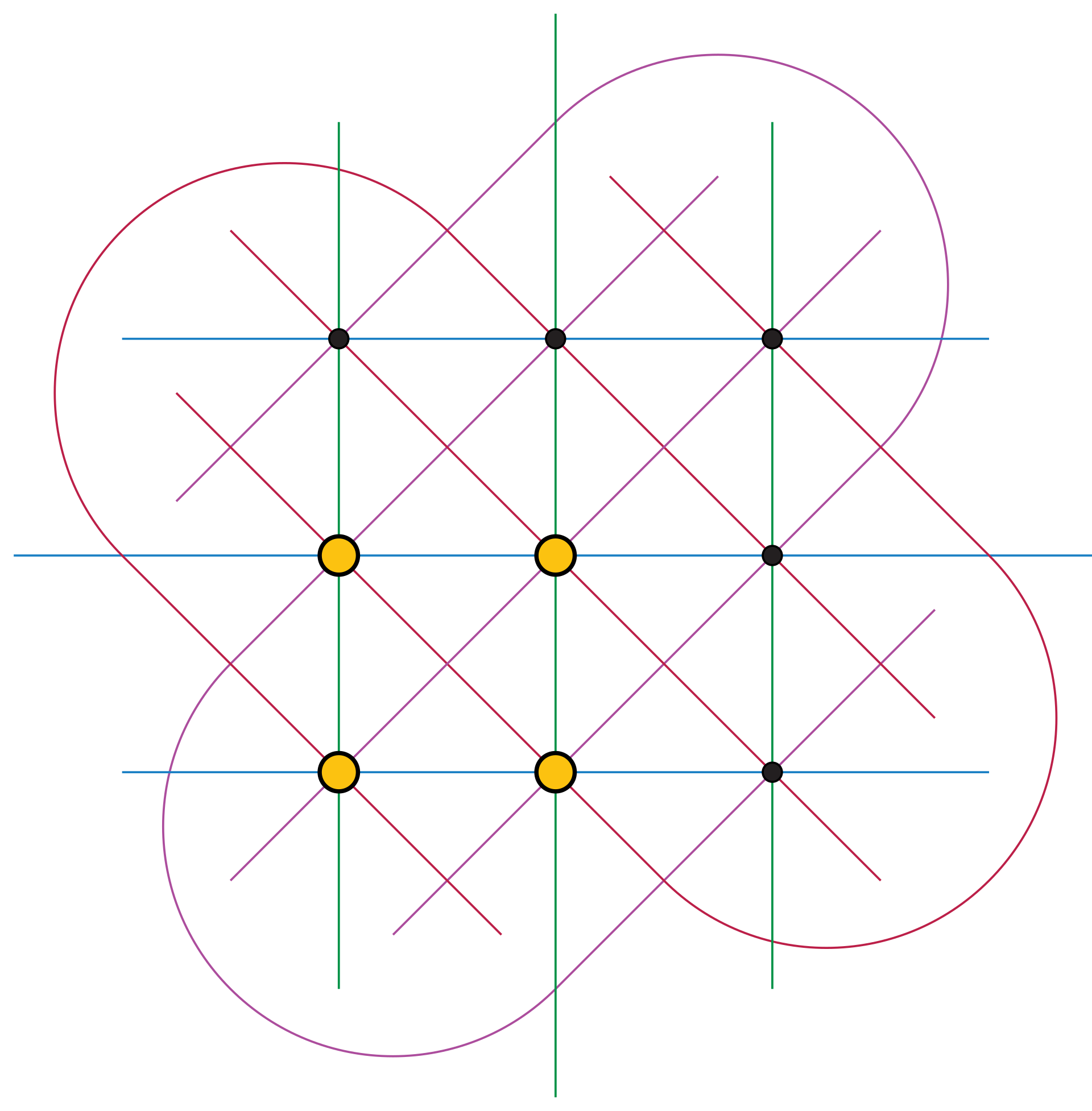

The cap set problem is less well known outside of number theory and extremal combinatorics. To state the problem baldly: a cap set is a subset $S \subset {\mathbb F}_3^n$ with no three points collinear - or equivalently no three points adding to $0 \in {\mathbb F}_3^n$. (I’m writing ${\mathbb F}_3 = {\mathbb Z}/3$ for the field with 3 elements.)

Then, for each $n$, what is the largest possible size $s_n$ of a cap set?

For example, the figure illustrates $s_2 = 4$. As an exercise, you might be able to see (by drawing some pictures) that $s_3 = 9$. Here are a few more values. But for most $n$, the exact value of $s_n$ is not known, and the game is mainly to improve on known bounds and asymptotics.

Well, it won’t surprise you that the authors of [4], using their LLM methods, improve on previously known results for $s_n$. In particular, for $n=8$ they improve the previously best known result $s_8 \geq 496$ to $s_8 \geq 512$.

Just before coming to the LLM methods behind this, why is the cap set problem interesting? I feel this needs a few words of background.

The story starts with the relationship betwen the prime numbers $2,3,5,7,11,\ldots$ and arithmetic progressions (APs) (whole number sequences of the form $a, a+d, a+2d,a+3d, \ldots$). A long time ago Dirichlet showed that every (infinite) AP with $a,d$ coprime contains infinitely many primes. In 2004, Green and Tao proved a sort of converse, that the sequence of primes contains arbitrarily long finite APs.

(For example $3,5,7$ is an AP of length 3. Here’s an exercise: find APs in the primes of lengths 4,5,…)

It is generally believed that this property results from the density of the primes in ${\mathbb N}$ as they go to infinity. Let’s say a subset $A \subset{\mathbb N}$ is dense if $\sum_{n \in A} 1/n = \infty$. Erdős had shown that the prime numbers are dense in this sense - and he conjectured that this property of being dense is enough to force $A$ to contain arbitrarily long APs.

Proving this conjecture turns out to be a hard problem. In fact, even the special case of APs of length 3 is not known. That is, if $A \subset {\mathbb N}$ is dense, does it necessarily contain a 3-term AP ${a, a+d, a+2d}$? Even this is not known!

The cap set problem arises from studying this 3-term case of the Erdős conjecture. Suppose that instead of looking at ${1,\ldots, N}$ as $N \to \infty$ we were looking at ${\mathbb F}_3^n$ as $n \to \infty$. (And it turns out that some arguments can be mapped between these two spaces.) Then a 3-term AP in ${\mathbb F}_3^n$ is exactly a line, and a subset $A$ without 3-term APs is a cap set. So the Erdős conjecture translates to a statement that a sufficiently dense subset must contain lines. To quantify this we need to understand how big a cap set can be.

Well, end of digression. If you needed convincing, this is roughly why the cap set problem is of interest to number theorists.

So back to the point: the DeepMind researchers were able to generate demonstrably new mathematical results. How exactly did they use an LLM to do this?

4. Using LLM as a search tool

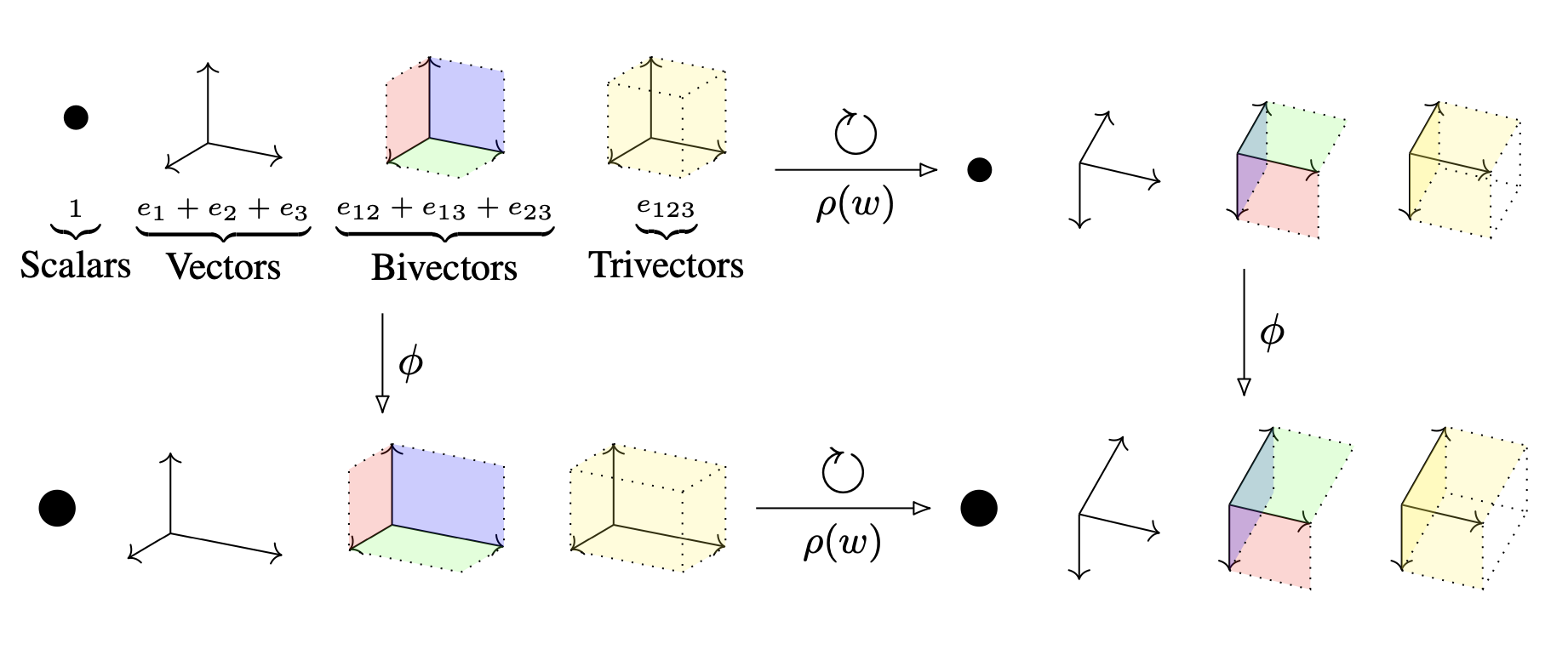

LLMs exhibit powerful capability to generate not just natural language text but also computer code - and code in response to natural language prompts. Take a look, for example, at the graphic at the top of this post. The unicorn pictures shown are the compiled images from TikZ code output by GPT-4.

The DeepMind work [4] has two key novelties. The first is that it approaches the problems bin packing and cap set by asking the LLM not just for solutions, but for code to generate a solution. The LLM used here, incidentally, is not GPT-4 but Google’s specialist Codey model.

So, for example, the model is not asked ‘what is the largest cap set you can find in ${\mathbb F}_3^n$?’ but rather ‘give me Python code to do the following …‘ More precisely, it is asked to complete a code template in which a particular function is to be filled in. For the cap set problem the template implements a greedy algorithm for building a cap set point by point, and the model is asked to fill in the crucial priority function that scores each candidate point for inclusion.

It goes without saying that this is a much more interpretable use of the AI: the code returned can be examined, understood and can inform subsequent mathematical analysis.

The second key novelty is that the LLM is not used for a single query, but for a sequence of queries, each of which seeks to improve on previous answers. So each query is not ‘fill in the priority function in this code template’, but rather, ‘given versions v0, v1 of the priority function in this code template, what should version v2 be?’.

The LLM is thus used not for one-time query but as an oracle step in an iterative algorithm. The full algorithm is evolutionary in the sense that a population of highest-performing codes is maintained, and the LLM prompts (the code versions v0,v1 etc) are drawn from this population.

The details of DeepMind’s evolutionary approach - their use of the LLM to develop a code to solve the original mathematical problem - are themselves very interesting. There’s no need for me to say more about them here as that is much better done in the blog [5] (and in [4]).

But the work sends a signal to the mathematical community, in my opinion, that there are very powerful new tools for us coming from language modelling.

References

- Sébastien Bubeck et al, Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4, arXiv.2303.12712 (2023)

- Long Ouyang et al, Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback, arXiv.2203.02155 (2022)

- Aerin Kim, RLHF: Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback Medium (2023)

- Romera-Paredes, B., Barekatain, M., Novikov, A. et al, Mathematical discoveries from program search with large language models https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06924-6, Nature (2023)

- A. Fawzi, B. Romera Paredes, FunSearch: Making new discoveries in mathematical sciences using Large Language Models, Google DeepMind blog, December 2023.