Neural networks in single-celled organisms

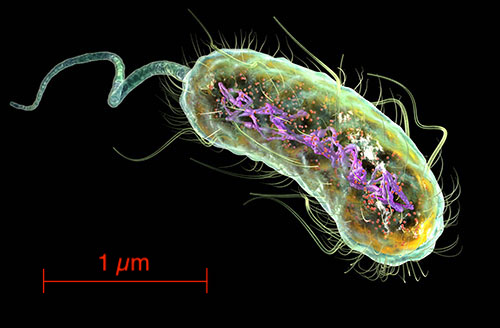

We tend to think of biological intelligence as arising from animal nervous systems and brains. But consider this. The bacterium Escherichia coli pictured above is about 0.5 micron across. Thousands could sit in the cross-section of a human hair. Notably, 0.5 micron is about the same size as a single synapse connecting neurons in the brain. Yet this bacterium can process information, exhibits short-term memory and makes decisions. It has to do so, as does every organism, in order to survive.

This blog post is inspired by, and heavily draws upon, Dennis Bray’s beautiful 2009 book Wetware [2], which describes how this information processing works (following [1]). The vast majority of organisms do not have nervous systems or brains, and yet they are able to exhibit biological ‘intelligence’. The biggest surprise for me in Bray’s account is how the molecular information processing that takes place in the cell can be modelled as a neural network in the same sense as understood in computer science. The units of the network are not nerve cells as we think of for animals (including humans), but are proteins.

Now, although artificial neural networks (ANNs) were originally inspired by the human brain, they are inevitably too coarse a model to represent what really goes on in the brain. In the machine learning community we understand that. We know that we’re not really modelling brains, but that ANNs are still a powerful computational device nonetheless - and underpin most of modern AI.

What is much less well known is that ANNs as a model are also a way to represent protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in the cell – and probably a much closer model of this than they are of animal brains.

A question it seems ripe to ask is: what lessons might this observation have for Artificial Intelligence?

TL;DR

- Clever cells: finding biological intelligence in microbes.

- Protein networks: how proteins implement neural networks in the cell.

- Lessons for AI: Artificial Intelligence has long drawn inspiration from biology - what can we learn from cell intelligence?

1. Clever cells

An E.coli bacterium is an autonomous agent (to use the language of AI!) moving in a fluid medium. Its method of locomotion is to rotate its ‘tail’, made up of a number of flagellae, each driven at about 100 Hz by a small molecular motor. The bacterium has two modes of motion: most of the time, all its motors rotate in the same direction, driving it at an approximately constant velocity in one direction. However, the bacterium can decide to reverse the direction of one or more of its motors, in which case it adopts an irregular ‘tumble’.

The bacterium also has molecular sense organs, which can detect up to 50 different chemical compounds at concentrations of just 1 part in 10 million. Some of these (e.g. sugars) it wants to steer towards; others (toxins) it wants to avoid. Evolution has equipped E.coli with information processing mechanisms (which I’ll come to in a moment) that allow it to detect chemical gradients and adjust its motion to increase concentrations of food and decrease the presence of toxins.

Over periods of sustained travel interspersed with tumbling in a viscous medium, the bacterium must regularly update its environmental assessment. In order to detect chemical gradients, it must both estimate concentrations and compare these with previous estimates. For this it needs some form of short-term memory. It must make decisions based on trade-offs between different (good and bad) chemicals present, and based on its current state of hunger, avoidance of threat etc.

Bacteria like E.coli have mechanisms to process information and convert sensory inputs (plus current internal state) into motor outputs, to achieve survival and reproduction in the competitive struggle with other organisms in the environment. They have clearly been successful in this over most of 3 billion years.

One can assume that their bevaviours are hard-wired by evolution (much like the bots I wrote about in an earlier post Zombie bots and neural bots). More sophisticated microbes, on the other hand, also show evidence of learning.

Protozoa are single-celled eukaryotes (cells with a nucleus) and are some orders of magnitude larger than bacteria such as E.coli. One of the best known, for example, is Amoeba proteus, a large predatory protozoan that hunts bacteria and other small organisms. Its mode of transport is different from the swimming of E.coli - it stretches out ‘arms’ called pseudopodia, via cytoplasmic streaming, and changing its whole body shape by flowing into one or more of these pdeudopodia.

Amoeba feeds by pursuing and ingesting prey which may itself be in motion. To do this, it needs to detect the location and movement of that prey. It needs to adapt its behaviour and mode of locomotion according to type of prey, and to coordinate multiple pseudopodia, both in the pursuit and to surround and engulf its prey.

Protozoa such as Amoeba respond to chemical gradients, mechanical vibrations, light, temperature, gravity. In other words, they exhibit sensory capability and attention. As they respond to their environmental state and move between distinct states of activity (feeding, travelling, resting, dividing etc), these creatures demonstrate responsiveness to the same range of sensory inputs as multi-celled animals, and the ability to make decisions on appropriate motor outputs. But without any nervous system!

It’s interesting to note in passing that individuality of behaviour is observed by researchers - with each bacterium (this is from [2], referring to E.coli) “displaying a distinct pattern of swimming”! This shouldn’t surprise us as random variation is the basis of evolution by natural selection. We also observe it in much simpler simulated systems too (see the earlier blog mentioned above).

Associative learning - that is, an organism’s ability to change its response to a given stimulus in the light of experience - is something we usually associate with brainy animals. However, it turns out there there is a long literature claiming associative learning in various protozoa including Amoeba. Many examples can be found in the references [3,4,5].

In summary, we can say that in evolutionary terms, biological information processing predated the evolution of nerve cells, nervous systems and brains by about 3 billion years. Not only that, but the capability of biological organisms to learn preceded nervous systems by maybe 1 billion years. In other words, brains and nervous systems are not actually fundamental to biological intelligence. Understanding what is could be illuminating for those of us thinking about artificial intelligence.

It turns out that the answer still seems to involve neural networks!

2. Protein networks

In this section I want to summarise Bray’s account in [1,2] of how information processing works in a cell to achieve the coordination, decision-making and even learning that we’ve seen above in bacteria and protozoa. The very surprising punchline is that the biochemical mechanisms we describe can be framed as instances of neural networks, in the sense of mathematical Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). (And I’m going to assume the reader is familiar with these.)

The key players are the proteins. Each protein molecule is built from a chain of amino acid molecules joined together - drawn from an ‘alphabet’ of 20 building block amino acids. The 20 amino acids have pairwise attractive and repulsive tendencies, and this causes a characteristic folding pattern of each protein molecule. This folding leads to the protein molecule having a geometry which may have binding sites that can connect to other proteins.

How do proteins interact? There are two fundamental physical mechanisms we need to understand:

The first is thermal diffusion, that is, Brownian motion by which molecules are randomly moving around the cell under heat energy, ricocheting off other molecules. The time scales for this are small: the time for a protein molecule to traverse an E.coli cell is around 10 milliseconds, or 100 times/sec.

When we speak of a protein $P$ in a cell we mean, more precisely, the population of all $P$-molecules in that cell. This may be in the region $10^4$-$10^6$ molecules. So under thermal diffusion, molecules of two proteins $P$ and $Q$ can be expected to meet many thousands of times per second.

The second physical mechanism to mention is what happens when molecules of two proteins $P,Q$ meet. In this event, one or other molecule can attach to binding sites of the other, via affinity of amino acids in the respective geometries.

In general, stable molecular structures in the cell are formed and maintained by ‘strong’ bonds (the making and breaking of which requires a significant transfer of energy). Protein interactions, on the other hand, are usually constructed by ‘weak’ bonds and geometric ‘recognition’. The strength of such a bond depends on the geometric goodness of fit.

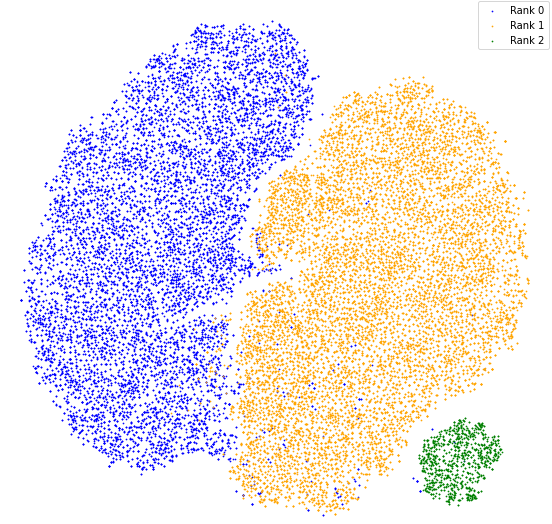

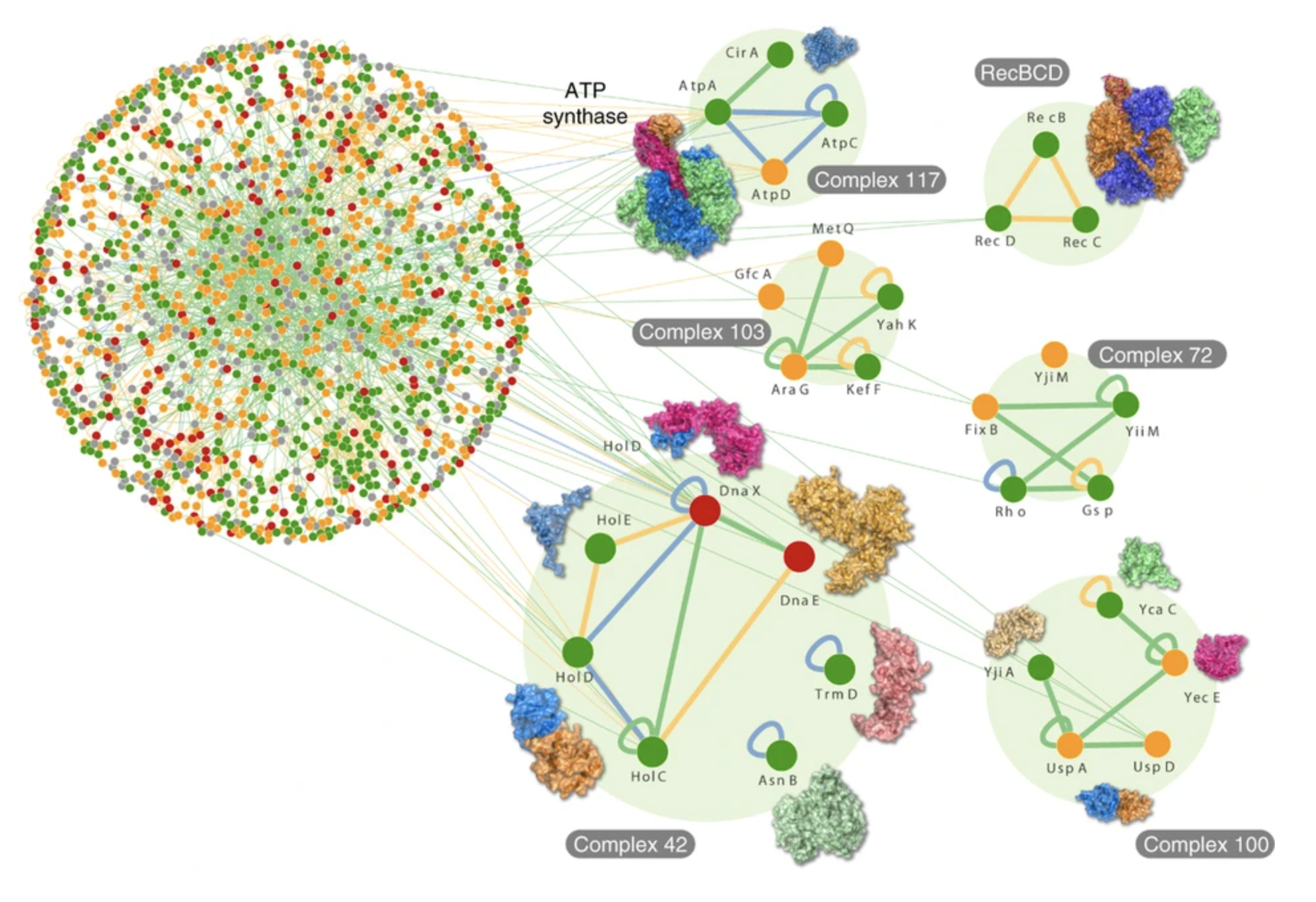

What I’ve described so far, at the most basic level, is how protein-protein interactions (PPIs) work. Just to illustrate the ‘social network’ of these, the following graph shows 2,234 binary interactions (edges of the graph) among 1,269 proteins (vertices) from the PPI network in E.coli:

The next thing to describe is how PPIs - weak binding of proteins through thermal diffusion and geometric recognition - leads to signals which allow propagation of information across a cell.

The key to this is that a protein molecule can exist in more than one (geometric) state. Recalling that the folding geometry of a protein $P$ depends on the net effect of mutual affinities of the amino acids in the constituent chain, it’s easy to see that in the presence of a binding protein $Q$ this total effect can change, so that the geometry of $P$ jumps to a different configuration. In this new configuration, new binding properties may appear, switching on or off interactions with other proteins.

The following diagram is taken from [2] directly, and shows a protein which functions as an enzyme (converting $A$ to $A’$) but under regulation by protein $B$. It has the signalling effect of a transistor:

To quote directly from [2]:

Two-state proteins are everywhere in a living cell ... they are the building blocks of flagella and cilia ... the molecular motors that harness chemical energy to make a cell divide, a muscle contract, an amoeba crawl ... They are at the heart of the electrical signals produced by nerve cells in our brain and hence underpin all our mental activities.

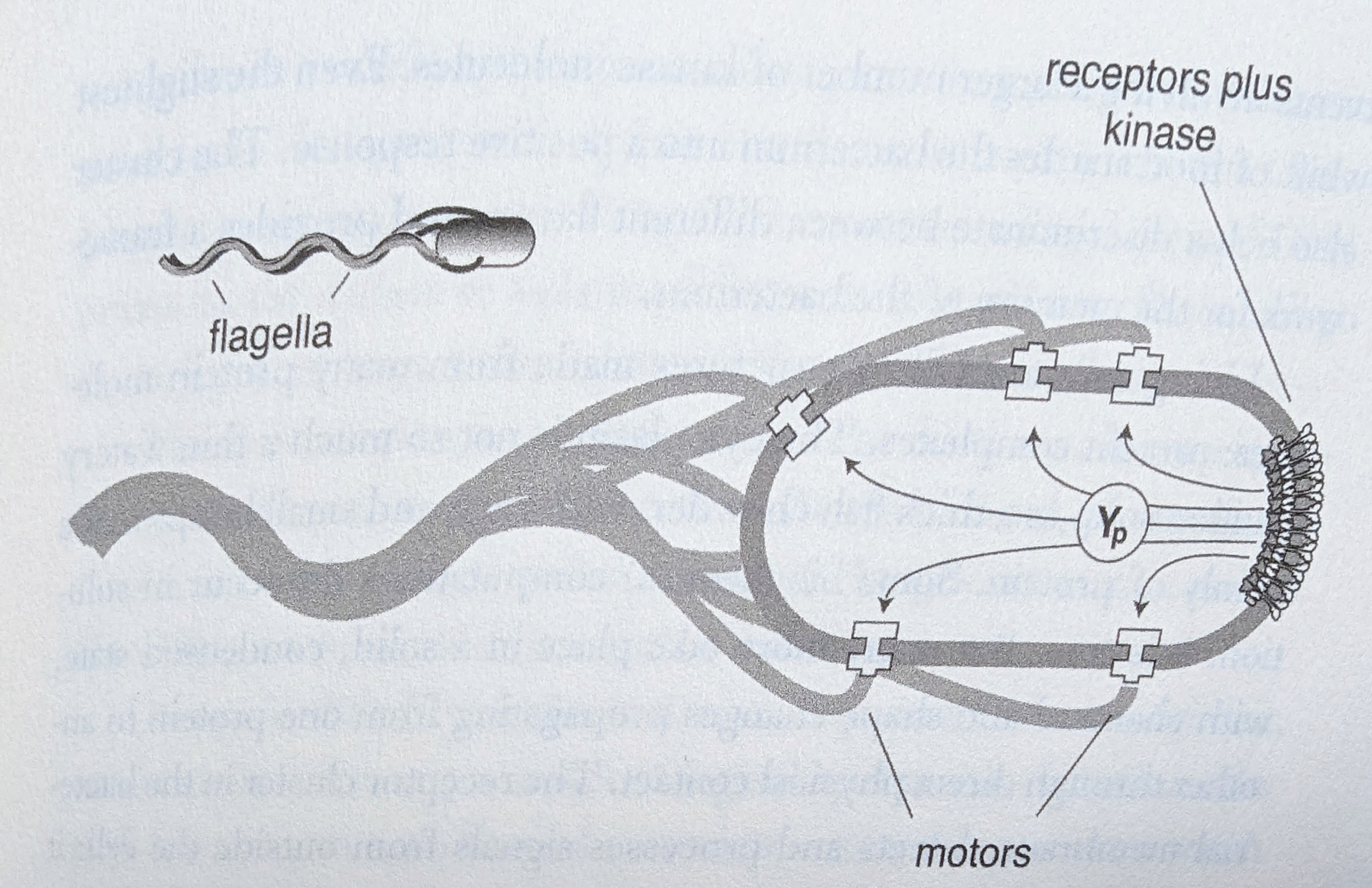

Some protein switches are held in ‘solid state’, for increased sensitivity or amplification, or for mechanical reasons. This includes the chemical receptors (signalling across the cell membrane) and the motors (which spin the flagella) in E.coli:

This diagram illustrates a general principle: any organism, to be independently mobile, must have sensory organs, some internal processing of those signals, and motor outputs that determine physical movement.

Detection of environmental signals is performed by receptors - protein switches embedded in the external cell membrane as shown above. Cells have hundreds of different kinds of receptors. Switching of a receptor by its target chemical on the outside of the cell activates its molecular function, initiating a chain of PPIs inside the cell.

(Inevitably, I’m skipping over lots of more complex detail. In particular, this includes efficiencies achieved by regulation of ‘third party’ background PPIs such as kinase-phosphatase cycles. But these all fall within the overall dynamical system of PPIs operating in the cell.)

Let’s turn to the internal processing - the decision making that processes the sensory signal and controls the operation of the motor proteins - how does this work?

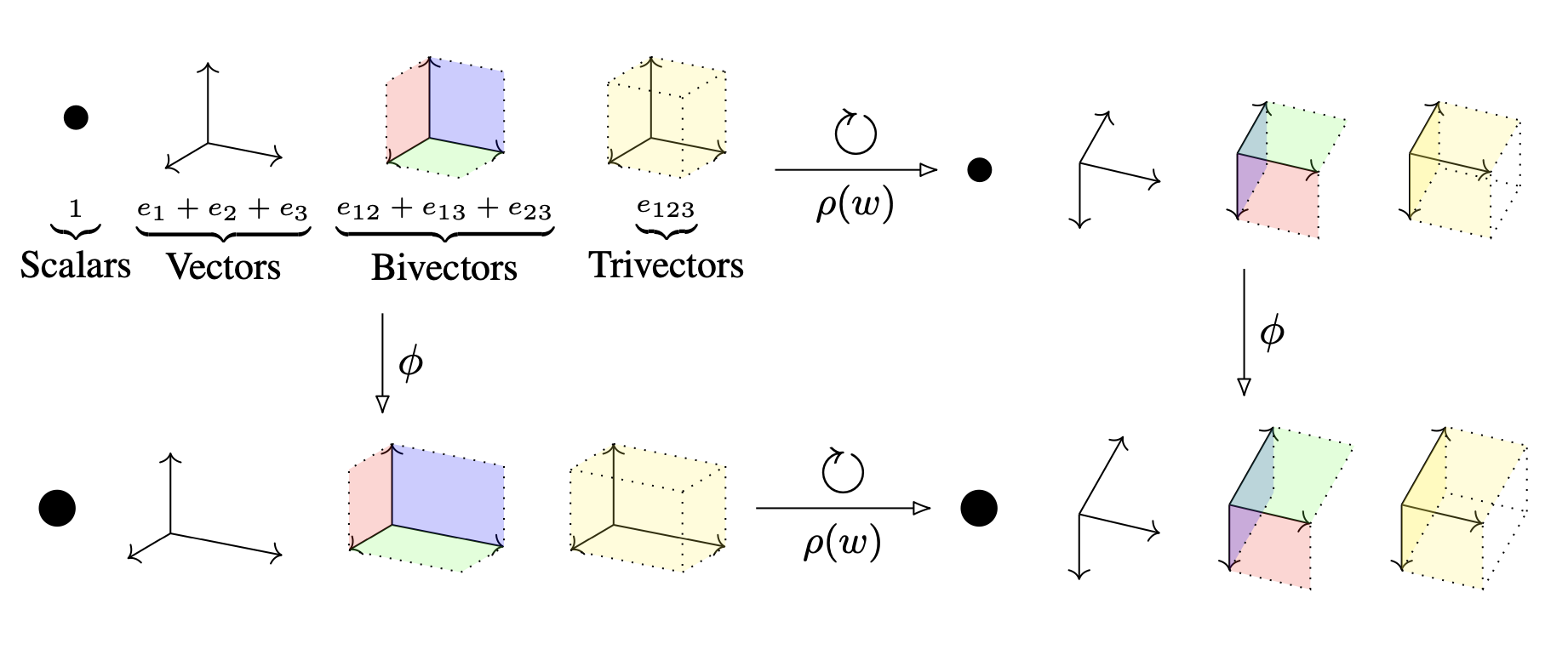

Bray explicitly recognises that the cell PPIs can be interpreted as a neural network, and illustrates the possible congurations of inputs/outputs with the following figure:

The modelling of each (protein) unit $P$ as a perceptron is explained in more detail in [1]. The inputs to $P$, at any point in time, are the concentrations of its incoming regulators. These are weighted by their catalytic efficiency as determined by binding strengths and other factors. The activation function is typically sigmoidal and the output of $P$ is its concentration at that time.

The network architeture is far from layered or feed-forward, but is inherently recurrent, including complex cyclic catalytic relationships among groups of proteins.

Of course, all models are simplifications and this is no exception. Units in the network are not all alike in their behaviours: each protein has its own characteristics including timescale of reaction and non-uniformity of distribution in the cell. Thermal diffusion operates at different timescales for smaller molecules compared to larger molecules; and proteins may exhibit localisation near, or impedance by, large-scale structures within the cell such as vesicles, filaments and membranes. So a good model might include per-unit parameters to allow for such factors.

What is the training process for a molecular neural network?

By far the most important training signal comes from the evolution of PPIs through natural selection. On the other hand, we’ve seen that cells can learn, and so there must also be mechanisms by which the weights of the network (rates of catalytic efficiency) can change in response to stimuli, allowing reinforcement learning. In multi-cellular organisms this is seen, for example, in cells of the nervous system and the immune system. Bray discusses some molecular mechanisms by which this may work - but I won’t discuss these here.

3. Lessons for AI

Most of us, learning for the first time about artificial neural networks (ANNs), were introduced to them as a simplified model of neurons in the brain. Research in AI and in algorithms has derived huge benefit from imitating biology, and neural networks have been one of the most successful examples.

However, what the work of Bray and others shows is that the ANN model has even greater depth and significance in biology than we realised. What conclusions should AI researchers draw from this?

One question to consider is the evolutionary relationship between molecular neural networks in single cells and multi-celled nervous systems in animals. Did the latter evolve independently and by coincidence? Almost certainly not: it turns out that key (PPI) signalling pathways that control motor behaviour in bacteria and protozoa were co-opted by evolution for use in the firing of action potentials between nerve cells. These collectively determine the computational processes in the brain.

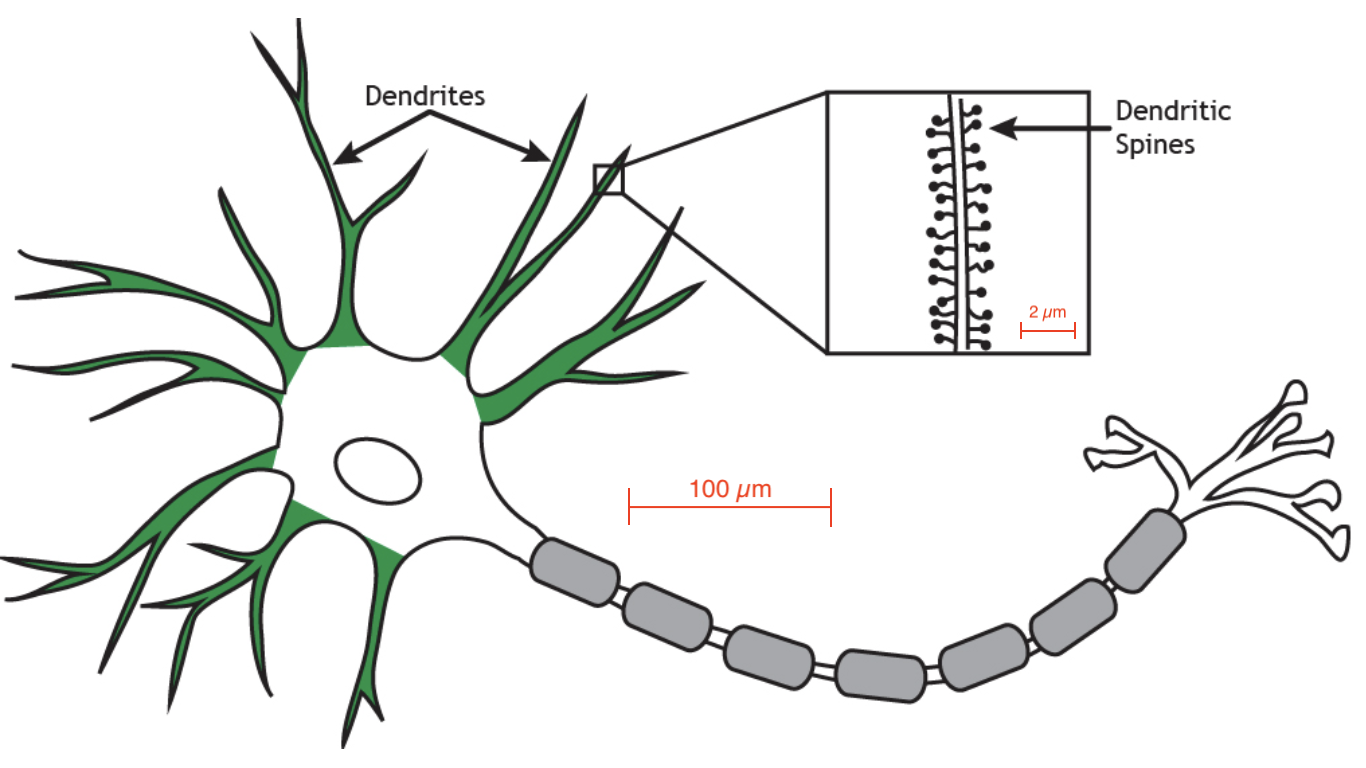

Consider this: a single dendritic spine - just one of a nerve cell’s 1000s of receptors for incoming axons - is about the size of a bacterium and operates, like a bacterium, by having a complex of receptor proteins embedded in its membrane. When the incoming axon fires, these receptors detect the neurotransmitter glutamate crossing the synapse. Some of the receptors can additionally detect the change of voltage within the spine that occurs when the receiving cell fires. This in turn can regulate an increase in sensitivity of that dendritic spine, driving a process of Hebbian learning for the formation of long-term memories in the brain.

In effect, evolution has adapted ancient and successful signalling PPIs to solve the problem of scaling - at least in animals. That is, the basic processes of thermal diffusion and geometric recognition of molecules are no longer sufficient for information processing at the length scales of multicellular organisms.

(Indeed, this raises a fascinating question for plants and fungi: these multi-cellular organisms must also process environmental information, and the mechanisms for this can also be expected to be derived from ancestral single-cell PPIs. Can their (macroscopic) solutions likewise be modelled as neural networks?)

So here is the bad news for AI. As long as we seek to model anything of the complexity of the human brain (or of animal intelligence more generally), artificial neural networks, even at the scale of current deep learning systems and large language models - and despite their success on the problems for which they are designed - can be expected to be fundamentally inadequate.

To highlight this point, I cannot do better than quote again from [2]. He points out that animal nerve cells are “self-contained entities … each a molecular metropolis in its own right”, and goes on to observe:

Imprisoned in the crowded confines of the cortex, your [brain] cells have no opportunity to escape. But there is nothing to stop them moving in place. They can grow and shrink, extend or retract their dendrites or branches of their axons. Their synaptic spines can be ... just as dynamic as an amoeba's pseudopodia. The movements of a nerve cell in the brain may be of shorter duration and harder to observe than those of a free-living cell, but why should they be less well informed? The milieu of such a cell is a rich and ever-changing broth of ions and neurotransmitters. There has been every opportunity for nerve cells evolving over millennia to learn how to extract information from this chemical soup.

Here’s the good news. The model of artificial neural networks, stumbled upon as a huge but very happy over-simplification of animal brains, turns out to be more fundamental in biology than we realised. It should be no coincidence, then, that it’s been so successful on such a broad range of hard tasks.

But evolving ANNs to models that get closer to AGI will likely benefit from a more subtle understanding of biological intelligence.

References

- Dennis Bray, Protein molecules as computational elements in living cells, Nature 376, 307–312 (1995)

- Dennis Bray, Wetware, A Computer in Every Cell, Yale University Press (2009)

- Philip Applewhite, Learning in protozoa, Biochemistry and physiology of protozoa (1979)

- De la Fuente, I.M., Bringas, C., Malaina, I. et al. Evidence of conditioned behavior in amoebae, Nat Commun 10, 3690 (2019)

- Samuel Gershman, Petra Balbi, Randy Gallistel, Jeremy Gunawardena, Reconsidering the evidence for learning in single cells eLife 10:e61907 (2021)

- Rajagopala, S., Sikorski, P., Kumar, A. et al., The binary protein-protein interaction landscape of Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol 32, 285–290 (2014)