Zombie bots and neural bots

We all know that neural networks are taking over the world. We see this in the deep learning revolution, in the wonders of deep reinforcement learning and of large language models. These advances combine Big Tech, Big Data and Big Bucks. But the underlying ideas are simple and very powerful, and in this blog I want to share some toy examples that I first played with about 10 years ago.

I’ll explain the animation above as we go — but basically the moving dot is a bot that’s evolved to seek out and eat red squares, using a brain with just 16 neurons, the output of which are shown, as time progresses, in the blue graph.

Everything is written in straight C++, with no TensorFlow or other advanced libraries. I’ll talk about the code in another post, but here I just want to focus on the ideas. All training will be by genetic algorithms (as I’ll explain) and not by gradient descent — this immediately simplifies things for us.

Here’s the task. A bot lives in a 2D binary array, and is to be programmed to efficiently find all the 1s (coloured red in the animations). At each step, the bot can only see 5 immediately adjacent squares (its own, and those to left, right, up and down); each of these can be in one of three states (0,1 or boundary (i.e. non-existent)). And it has 5 actions to choose from: move left, right, up or down, or ‘eat’ the (value of the) current square.

The first type of program we might think of — let’s call this a zombie bot — consists simply of a 3⁵ = 243-long lookup table of moves, such as:

304103402202214122102102401303313302201214404102104044203101340202201110102102131401314403344204304401104402441113401241114400300214110441400423443014321343143134201104301204102220314421441333434304333332331233340312101100402201101131422114214

In other words, for each one of the 3⁵ possible states, just look up the corresponding number from 0 to 4 and take that as the action to follow.

Challenge: can you design this ‘program’ — i.e. the sequence of digits — to get an optimally efficient bot? (Well, it turns out that optimality is impossible, as we’ll see in a moment.)

Let’s suppose you’ve done that, and are ready to test your solution against nature’s. So what might nature’s be? Here’s a genetic algorithm approach:

Let’s call the above lookup table the bot’s genome, and assume that two bots are able to have sex (resulting in two children) by choosing a random partition of their genomes, swapping alternating portions, and then applying some low-probability mutation to each offspring. We then initialise a suitably-sized population, implement sex freely in that population, and retain at each generation only those bots with the best ability to collect 1s (i.e. find red squares). In other words, we’re running a genetic algorithm to optimise a fitness function (which consists of a suitable test regime for hopeful bots).

OK … so here’s a typical zombie bot after 10 generations of evolution from a random initalisation ![]()

And after 500 generations ![]()

And after 2000 generations ![]()

At this point — quite surprisingly — the bot has evolved a ‘reconnaisance’ strategy. You might notice that sometimes when the bot enters a patch of red, it doesn’t start eating immediately, but instead travels to one end of the patch, and then systematically eats its way back across the whole patch. This is clearly a better strategy than to arbitrarily eat in one direction or the other, which would create two islands one of which it cannot easily find its way back to. (Did your hand-crafted program think about this?)

The zombie bot is therefore well adapted to its task — but it’s not optimal. At the end, it finds itself running round the boundary, unable ever to find its way back to the interior to explore for left-over bits. Since it runs on a fixed lookup table, this is inevitable.

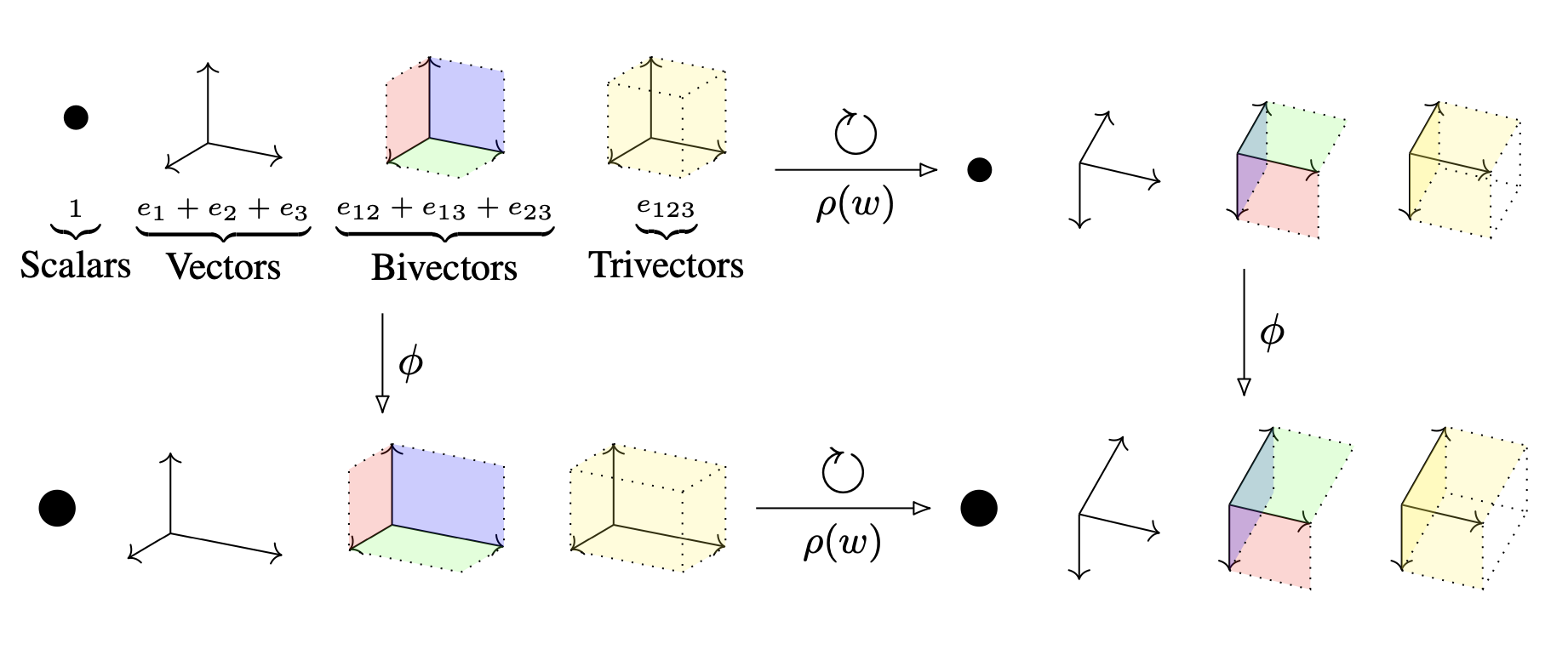

Now meet the neural bot. This has a genome consisting of 416 real numbers, which are weights of a recurrent neural network with 16 hidden units:

This is the very simplest type of recurrent neural network — and as the diagram suggests, we interpret the input bit vector as defining the current ‘sensory’ state, and the output as defining a ‘motor’ decision.

(Today, recurrent networks have evolved beyond recognition from this simplest version — from LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) and GRU (Gated Recurrent Units) to today’s Transformer models. But many of these advances were in response to the challenge of training by gradient descent — for a small task, our example avoids that problem altogether by training with a genetic algorithm.)

Treating the weights of the network as a ‘genome’, we can now evolve the neural bots in exactly the same way as their zombie counterparts. As we do so, we have at any point in time a population of bots, and we can observe them as individuals. We find that even at this very simple level they demonstrate different ‘personalities’. Here are two examples:

The first is the one pictured at the top of this post (accompanied by the output of its 16 hidden units at each time step). Take another look.

This bot is able to move diagonally. That would be impossible for a zombie bot, for which the state uniquely determines the action. And consistent diagonal action requires short-term memory, which is somehow encoded in its 16-bit brain. The bot chooses between diagonal and straight-line travel, in the quest to hoover up red squares.

The second bot I want to show you is lazier, and has evolved a near-optimal strategy of simply marching up and down, systematically ignoring the bits in the next row it’s coming to. Its laziness (or efficiency) is even visible in its mental state: it clearly has more brain cells than it uses!