COP26: seeing the wood for the trees

The climate crisis poses an almost overwhelming challenge to humanity, and it is very easy to be pessimistic. But there are also some reasons to be hopeful. Many will have been inspired by Prince William’s Earthshot initiative, by the vision behind it and the passion and creativity of the finalists and other innovators. It gives me genuine hope that we have the capacity to correct our course for a safe future.

You will hear about many innovations and tech solutions for sustainability in the margins of COP26. However, the success of the conference will stand or fall on one thing only: the ability of the international community to agree a practical pathway to achieve the 1.5°C goal of the Paris agreement.

This is ultimately a numbers game. One of the most hopeful conclusions from the 2021 IPCC 6th Assessment Report is that there is a strong linear relationship between the average global temperature we arrive at this century and the total volume of carbon that we emit into the atmosphere from today. In other words, the world has an emissions ‘budget’: the lower the budget, the lower the final temperature rise.

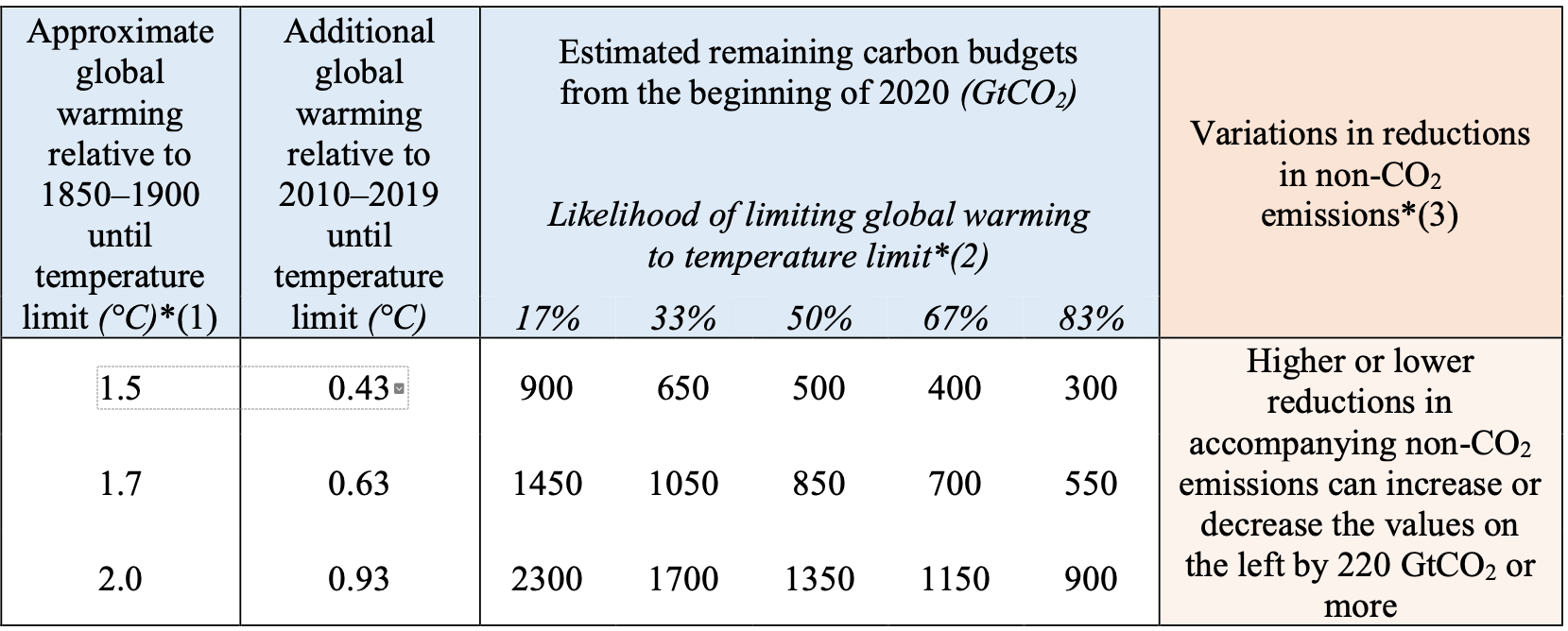

To understand the budget choices, the following table is from the IPCC report:

The table expresses uncertainties and margins of error. Sorry. But it’s the best science we have to go on, so let’s see what it says.

The rows of the table express budgets (in GtCO2, or giga-tonnes of CO2 emission) for limiting the global temperature rise to values on the left-hand margin, with likelihood expressed in the top margin. So, for example, 500 GtCO2 buys a 50% chance of staying within 1.5°C in this century. Let’s go with that for the moment – assuming a 50% chance feels a safe enough bet for you.

So how much is 500 GtCO2? For comparison, the world in 2020 released approximately 40 GtCO2 (with the UK responsible for about 0.3 GtCO2 of that). So at current rates, 500 equates to about 12 years. Or if we could assume a 7% worldwide reduction in emissions every year, then it buys us 30 years.

(Two more comparisons: the proposed coking coal mine at Woodhouse Colliery would commit the UK to about 0.16 GtCO2 from the coal extracted over the lifetime of the mine; the Cambo oil field in the North Sea commits us to about 0.3 GtCO2. Both would eat significantly into any reasonable budget for the UK.)

This is the numbers game that COP26 has to solve in order to ensure a safe future. What emissions budget can the international community agree that will set an acceptable level of temperature risk? Given that budget, how will it be divided equitably among nations? And how do we support poorer nations to live within their budget as they transition to a zero-carbon future?

All too often, responding to the climate crisis is framed as being about personal choices (you should fly less, you should eat less meat). It isn’t. Ultimately, it depends on science-driven policies, tireless diplomacy and international cooperation to shift those big carbon numbers. COP26 is a critical part of that process.

Yes, our lifestyles will change, and individual choices are important – but for the majority they’ll change the way they always have done: in response to better choices coming along through vision, investment and legislation.