COP26: the climate crisis today

This is the first of three blogs in which I’d like to share a few thoughts on the climate crisis and on the COP26 conference which launches in Glasgow this week. In the second blog I’ll say a bit about the figure of 1.5 degrees warming and what it means; in the third I’ll focus on COP itself.

But let’s start with today. As we look back over the summer of 2021, we’ve seen a number of tragic events in the news: the Pacific North-West of the US and Canada was hit by a ‘heat dome’ killing more than 500 people – as well as up to a billion marine animals. Southern Europe was hit by record wildfires killing many people in Greece, Italy and Portugal. Wildfires in Siberia were reported to be larger than the rest of the world’s combined – as rain was observed on the summit of the Greenland icecap for the first time. During the same few weeks major floods hit China (302 deaths), Germany (196 deaths), Belgium (42 deaths), Mexico (17 deaths) and Pakistan (160 deaths). Back in the US, hurricane Ida travelled up the east coast from Louisiana to New York with a death toll of 82.

This is just a snapshot of recent times. The climate crisis, and our response to it, is not just about ‘saving the planet’, it’s about saving lives. And extreme weather is not a ‘new normal’ – because the Earth system is in a state of transition and will take many decades, or even centuries, to settle into a new stable state.

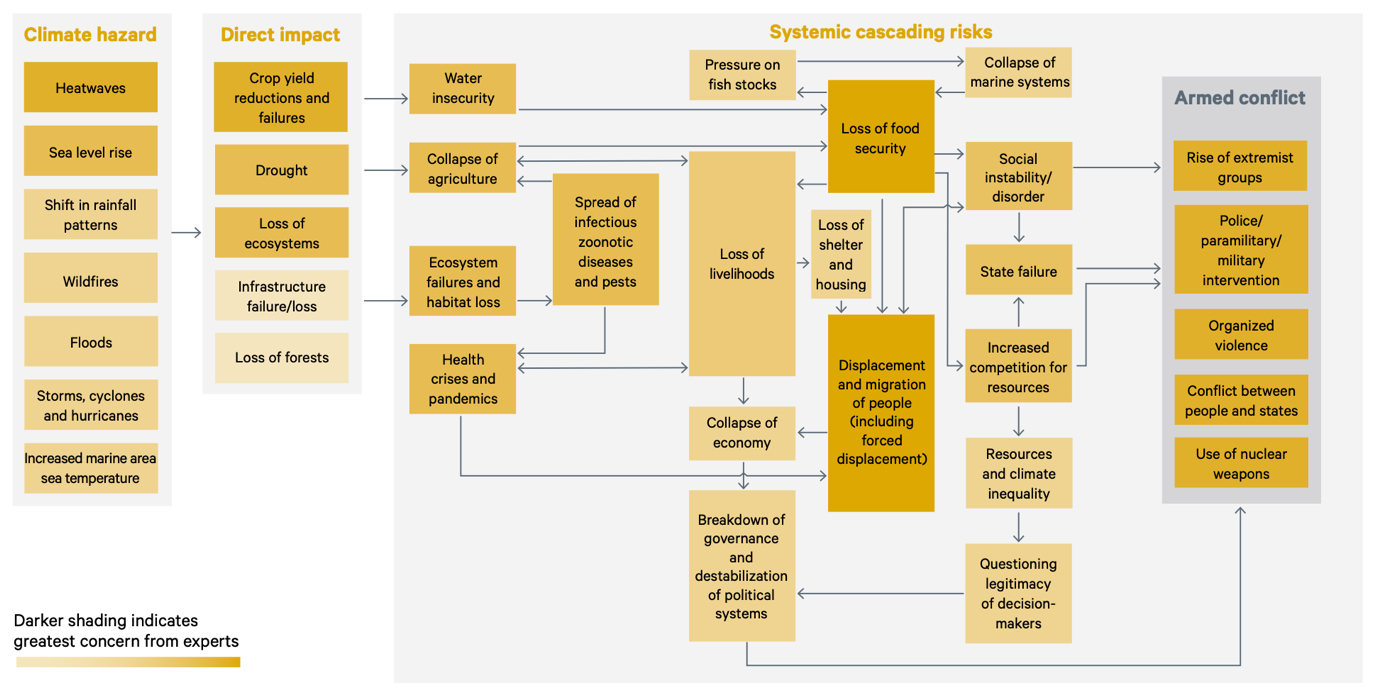

The climate crisis is also about national security. Our security depends not only on safety from wildfires and floods, but also on resilient infrastructure, a stable economy and secure food and water supplies. It depends on stable international relationships and supply chains and the ability of our people, from tourists and business people to diplomats and military personnel, to travel and operate safely overseas.

The evolving threat around the world is not only from extreme weather events. It’s also from changing rainfall patterns and failing agriculture, from depleted water sources and from sea level rise and storm surges. It will drive tensions over these resources and over displaced populations. The graphic at the top of this post, illustrating some of these cascading risks to security, is taken from a recent Chatham House report.

According to the World Climate and Security Report (WCSR) 2021, “within the next twenty years, security risks stemming from climate phenomena will present severe and catastrophic levels of risk”. That’s a stark message, and I shall offer a bit more optimism in the third of these blogs. But there is no doubt that as the crisis unfolds it will affect the politics, rivalries and stability of all nations.

Examples cited in the WCSR report include: floods in Sudan in 2020 exacerbating the country’s already fragile security infrastructure, as well as requiring assistance from the Egyptian military for humanitarian aid; the impact of recent floods and wildfires on US military bases and equipment; and increased tensions in the Arctic. China’s economic dominance in the 21st century is argued to be “not guaranteed” because of the dense concentration of population and economic hubs in cities most at risk from sea level rise and from water shortages. Russia may perceive that it is less at risk from climate change than other countries, yet it is vulnerable both from the threat to infrastructure of melting permafrost, and from exposed fossil fuel assets if the world succeeds in shifting rapidly to renewable energy sources.

These are just examples of the ways in which the climate crisis will have deep implications for behaviours and intents of nation states. So the COP26 conference matters to us. It is a milestone event which will have huge implications for the direction that humanity takes. I’ll say a bit about the problem it has to solve in the next two blogs.