COP26: why 1.5 degrees?

In the 2015 Paris Agreement, countries of the world signed up to “keep the rise in average global temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and preferably limit the increase to 1.5°C”. This month’s COP26 summit is the last best chance for nations to agree plans of action to achieve that goal. For the reasons I discussed in the previous blog, it’s vital for all our futures that we succeed.

So why 1.5°C? The figure sounds insignificant – what does it mean?

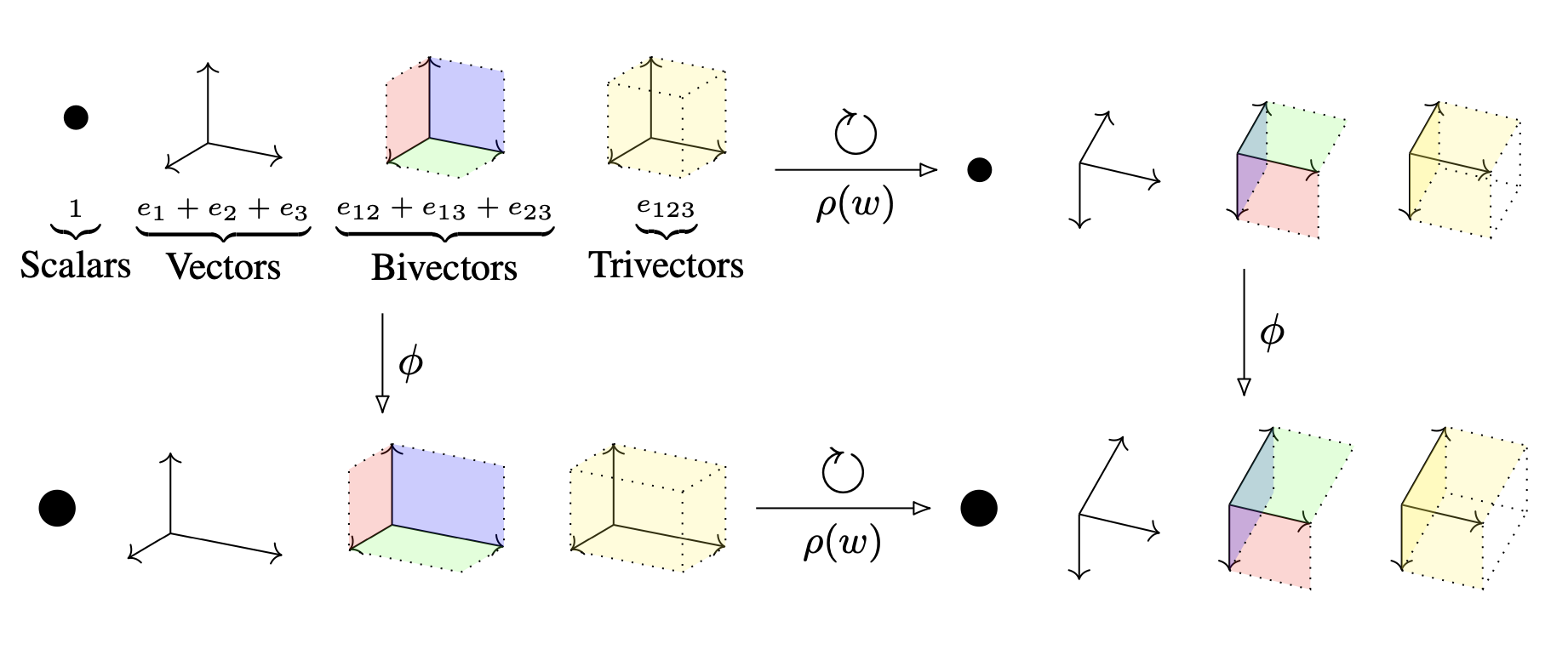

Global average temperature is not a flat, uniform thing. It’s more like the surface of the sea – it has peaks and troughs. And actually, as the average rises, so does the variation between those peaks and troughs. The graphic above, taken from the Atlas of the Invisible, illustrates this. Each square is a little map of the Earth, showing average temperature from 1890 to 2019. The colour, from blue to red, shows how far the temperature is below or above the global average for the ‘baseline period’ (1960s to 1980s). What you see is not only the trend but the variation across the planet.

So a total average temperature rise of 1.1°C (above the pre-industrial average, which is roughly where we are today), affects different parts of the planet in different ways, and has led to the big effects in terms of extreme weather, melting ice and changing rainfall patterns that we see today.

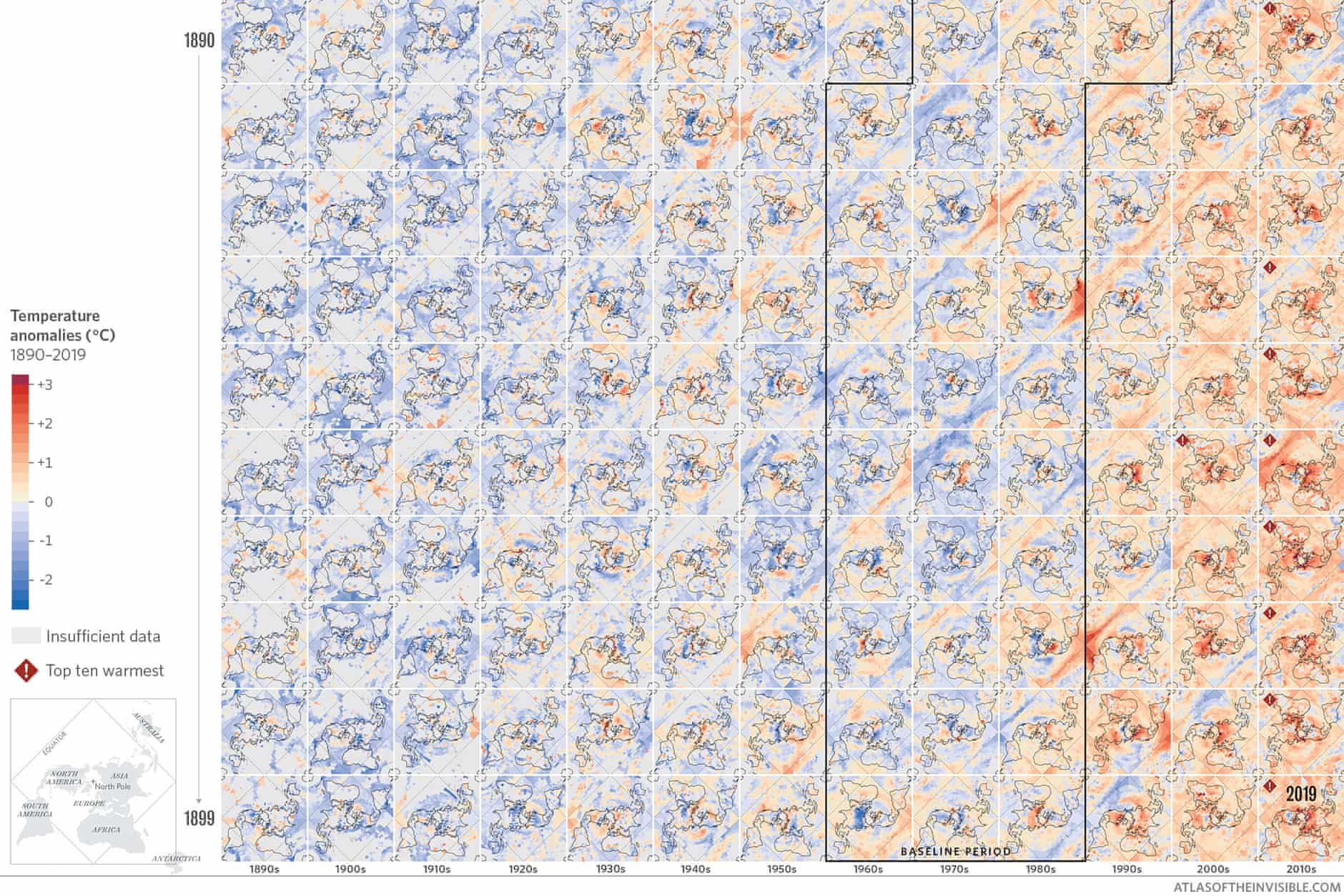

Let’s put that figure of 1.1°C in historical context. The following graphic is taken from the IPCC’s 6th Assessment Report this summer. It shows that insignificant-looking temperature difference in the context of the last two thousand years. In this context, we see that 1.1°C is a very big deal and that the rise is not gradual but is better thought of as a shock to the system.

The graphic also shows that today’s temperature is outside anything the planet has experienced in the past 100,000 years. At 1.5°C we will already head beyond any conditions that have existed during the lifetime of our species. Yet the IPCC report makes clear that we are very likely to exceed 1.5°C by 2040 and possibly by 2030. Without radical actions agreed at COP26, according to the IPCC, we are heading past 2.4°C by 2040 and to around 4.0°C by the end of the century.

A temperature rise of 4.0°C is pretty unthinkable. In geological time it takes us back nearly 50 million years to an age before primates had evolved and when the poles were temperate. The sea level rise this would induce would drown all the major coastal cities in the world.

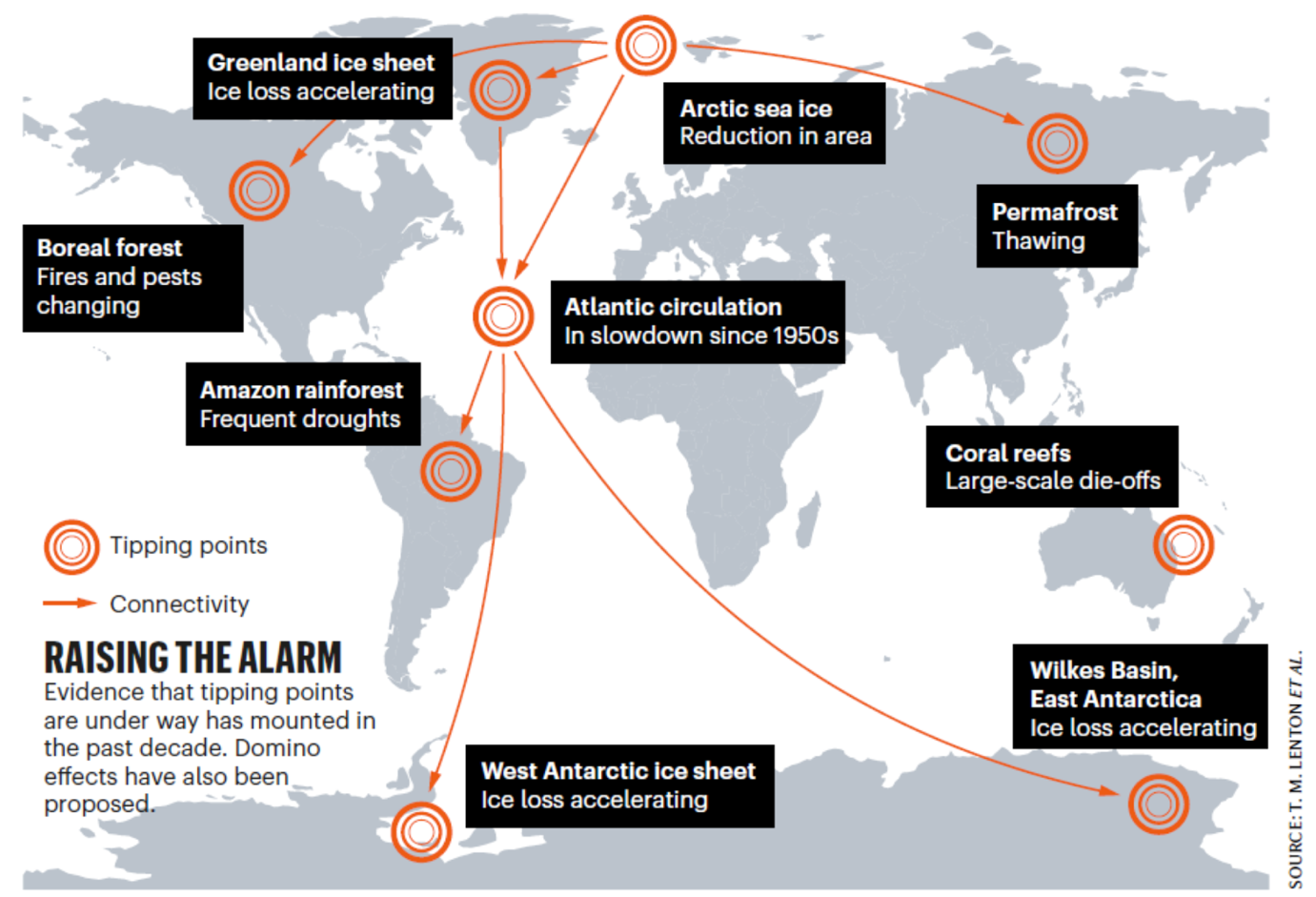

A major risk of permitting uncontrolled temperature rise is the existence of tipping points in the Earth system – temperature levels at which global processes will kick in that would send the temperature rise higher still. The graphic below, by Tim Lenton, illustrates these tipping points.

So the threats are real and current climate change is very much a crisis. But it is still not too late in the day, and there is no doubt that humanity has the ingenuity and resourcefulness to rise to the challenge. Rising to the challenge is just what we have to look to COP26 to do.

The problem to be solved is stated as a number, 1.5 degrees – so any solutions have to play a numbers game. I’ll talk about that in the last blog.