Language barriers in global conservation

Wildlife tends not to respect national boundaries. Birds, in particular, as they migrate across and between continents, ignore not only borders but even the cultures and languages of the scientists who may be trying to study and protect them. And, surprise surprise, not all of the world’s science is written in English.

According to a recent study [1], more than 30% of scientific articles on biodiversity conservation are written in non-English languages. Moreover, the authors claim that non-English language scientific outputs – at least within biodiversity conservation – are increasing both in volume and in quality. In geographic regions where English is not widely used – as in some of the world’s biodiversity hotspots – key data and evidence are generated by local scientists and even by citizen science projects in local languages. So when it comes to tracking species with global geographic ranges, restricting only to English-language scientific outputs can lead to key gaps in knowledge.

The study [2] takes a closer look at this issue for bird species. They compare the known geographic ranges of more than 10,000 species with the official languages listed for the countries covered by those ranges. They show that more than 1,500 species have coverage of at least 10 languages. High numbers of ‘multi-lingual’ species have ranges spanning Eastern Europe, Russia and central Asia. Nevertheless, they also observe that four European languages – English, Spanish, Portuguese and French – dominate species coverage globally, each reaching between 3,000 and 6,000 bird species.

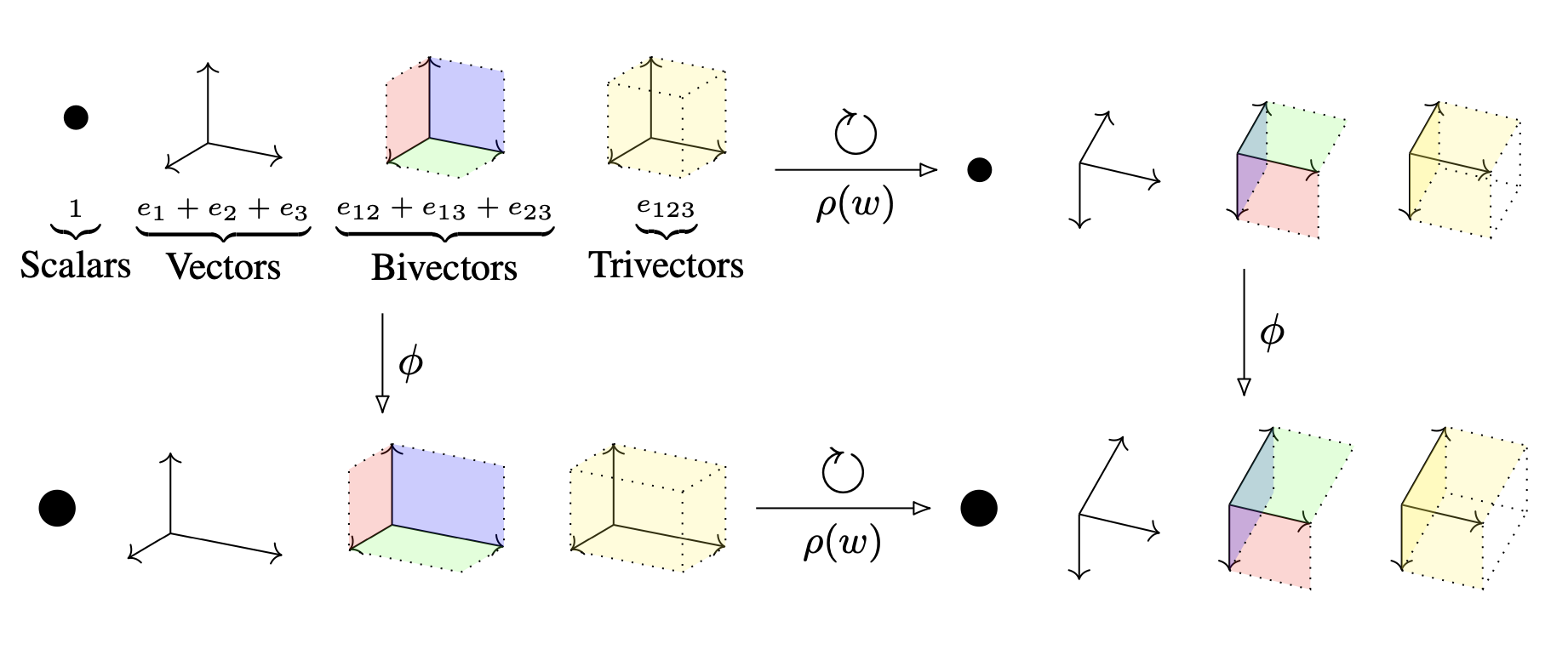

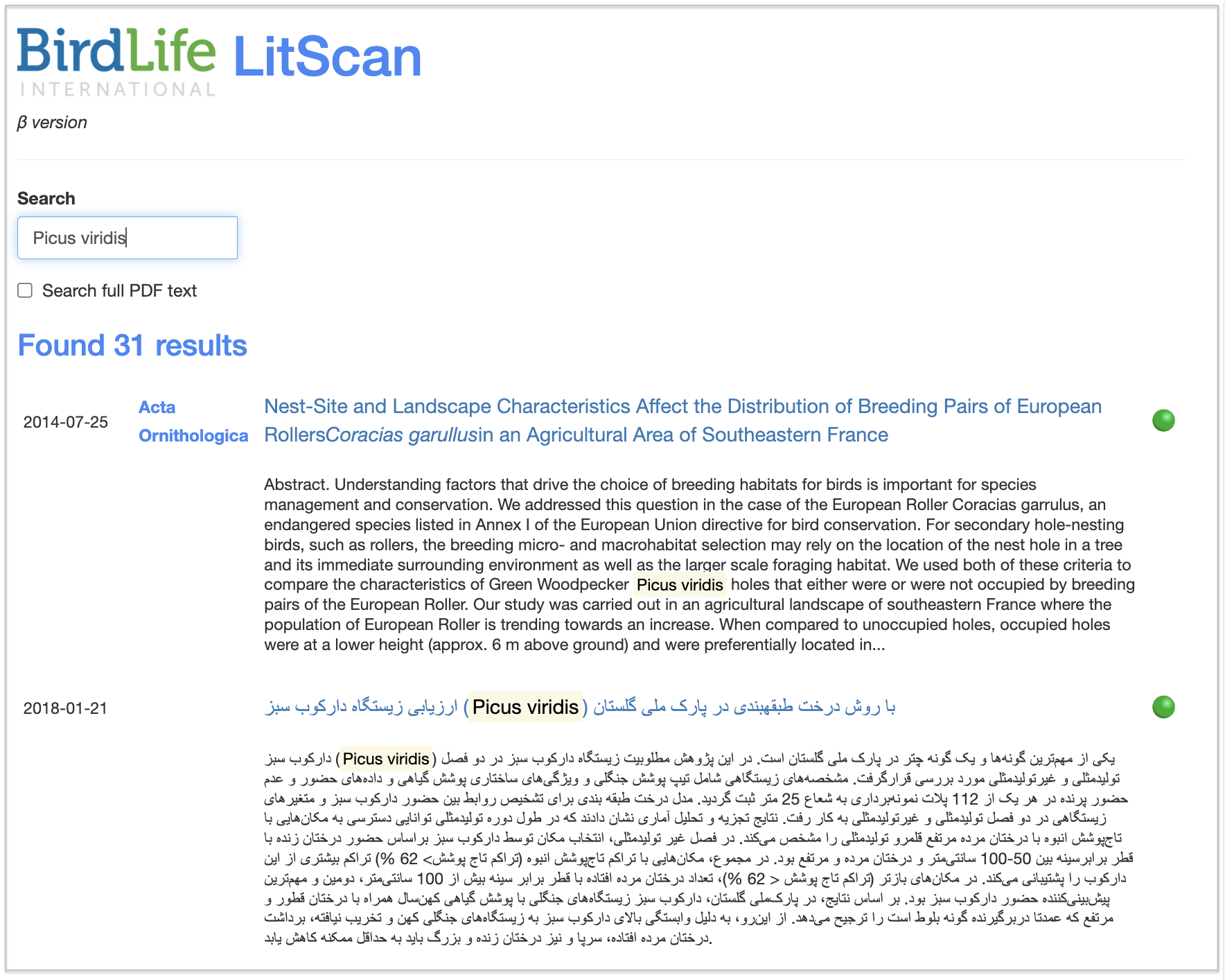

In a project for BirdLife International, I have been able to put some of these observations to the test, from the complementary perspective of what can be seen directly in the scientific literature. LitScan is a system to crawl and identify scientific articles of relevance to Red List assessments. It scans various sources across multiple languages; makes use of spaCy for text-processing (including language id, discovery of species mentions and conservation relevance); and uses Cloud cognitive services for translation.

For the purposes of this blog post – and for comparison with the results of [2] – I want to focus on just one of the LitScan sources OpenAlex [3]. This is an extremely useful open-source repository of metadata for scientific documnents drawing on an impressive range of sources. I don’t know what the exact language coverage of OpenAlex is (and I’m sure it could be improved), but I can make some observations based on LitScan.

(Incidentally, besides OpenAlex, LitScan taps directly into various non-English sources. These are quite specific and would bias any comparison with [2], so in this post I’ll just restrict to LitScan data that comes from OpenAlex.)

So here’s a data set – used by LitScan but constructed as follows. Over a 3-month period a daily request was made to OpenAlex. The request consisted of 500 searches, each on the scientific name of a bird species drawn at random from a list of 11,188. The searches are not all successful, and over the collection period the number of documents returned – after some additional filtering for conservation relevance and publication since the year 2000 – was 35,303 (so averaging about 400 per day).

The total number of species covered by these documents was 3,517, in a total of 32 languages – by far dominated by English (32,239 documents), with the next most numerous language being Spanish (824 documents).

We can now ask, in the spirit of [2]: how many species are found in non-English documents only? Moreover, since we are interested in conservation relevance, we can ask for this number broken down by red-list status – as defined by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – as well as language:

| LC | NT | VU | EN | CR | EX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | 211 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Portuguese | 52 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Indonesian | 29 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| French | 25 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| German | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Korean | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mandarin | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Czech | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Catalan | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Norwegian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Croatian | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

(The columns are the red-list categories Least Concern, Near Threatened, VUlnerable, ENdangered, CRitically endangered and EXtinct.)

These are small numbers, but every species counted in this table represents information that may be lost to red-list assessors who have access only to English-language science. Moreover, many more species are represented in both English and non-English documents (and so are not counted here).

The document sampling using OpenAlex is far from unbiased – clearly we have not tapped into a much wider literature in, say, Mandarin or Korean. The LitScan ambition is to maximise the use of sources in those languages directly in the future. Nevertheless, the analysis offers an interesting corroboration of the observations in [1,2].

References

- T. Amano et al: Tapping into non-English language science for conservation of global biodiversity, PLOS Biology (2021) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001296

- Pablo Jose Negret, Scott C. Atkinson, Bradley K. Woodworth, Marina Corella Tor, James R. Allan, Richard A. Fuller, Tatsuya Amano: Language barriers in global bird conservation PLOS One (2022) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267151

- Priem, J., Piwowar, H., & Orr, R. (2022). OpenAlex: A fully-open index of scholarly works, authors, venues, institutions, and concepts (2022) arXiv: arxiv.org/abs/2205.01833