Predicting the rank of an elliptic curve

Of all the hype that attaches to machine learning these days, among the least trumpeted applications - but to my mind some of the most interesting - are those applications of machine learning to mathematics itself. In this post I want to talk about an application demonstrated in the paper [1] Murmurations of elliptic curves. I will discuss some experiments of my own reproducing the results of that paper.

Spoiler for the graphic above: each dot represents an elliptic curve over ${\mathbb Q}$ coloured by the rank of the curve; its position in the plane depending only on the numbers of points on the curve modulo the first 100 prime numbers. (I’ll explain all this as we go!)

The subject requires quite a bit of background, but it’s a story worth telling: it relates closely to a problem, the Birch-Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture, which is one of the seven $1,000,000 Millennium Prize Problems announced by the Clay Mathematics Institute in 2000.

Let’s start with:

What is an elliptic curve?

An elliptic curve is essentially a plane curve defined by a cubic equation in coordinates $x,y$, for example \[ y^2 + xy + y = x^3 - x^2 - 9916x - 377564. \] The coefficients can be any real or complex numbers, but in this post I’m only concerned with curves with coefficients in the rational numbers ${\mathbb Q}$, as in this example. These are called elliptic curves over ${\mathbb Q}$.

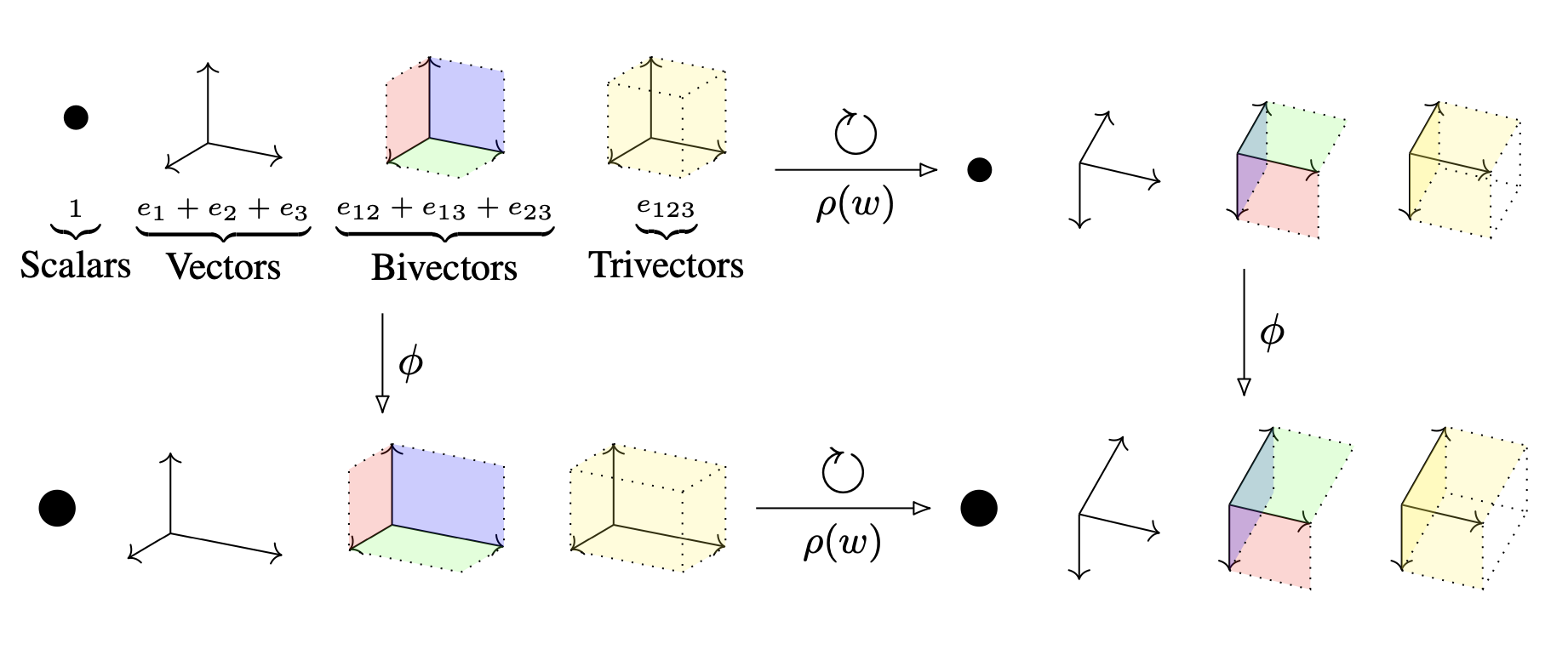

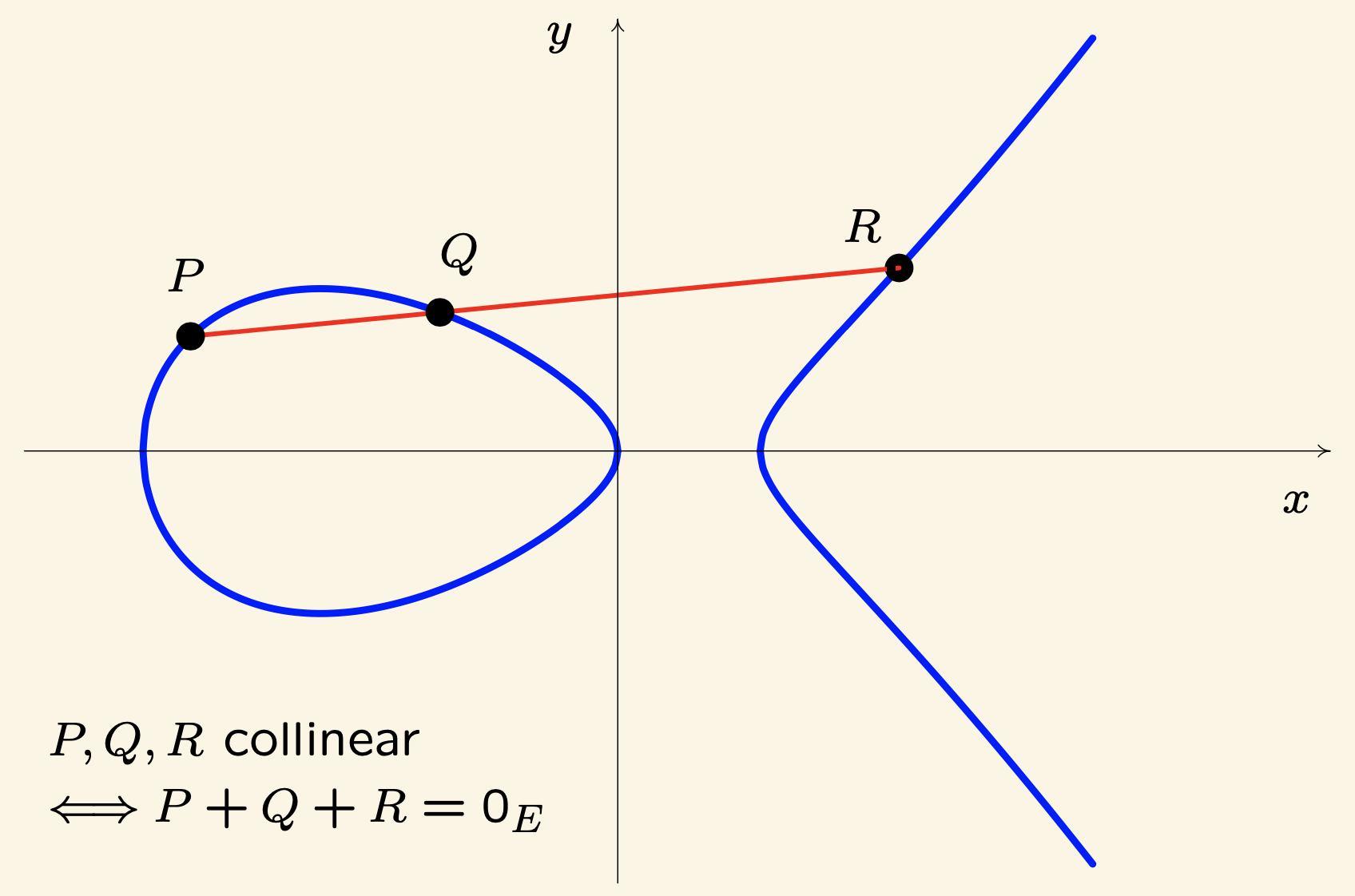

Elliptic curves have both a long mathematical history and a surprising modern relevance - both on account of the fact that points on the curve naturally form a group, via the rule that three points are collinear in the plane if and only if they add to zero in the group law:

(The identity element $O_E$ is usually taken to be the point at infinity on the $y$-axis.)

The modern relevance of this is the use of elliptic curve groups in digital security. The mathematical relevance is in understanding the structure of this group for any given curve. (And, of course, the mathematical theory is critical for the secure use of elliptic curves in encryption and signature schemes.)

What is the rank?

The rational points on an elliptic curve $E$, which we denote by $E({\mathbb Q})$, form an abelian group - that is, the group is commutative $P + Q = Q + P$. Moreover, the Mordell-Weil Theorem, proved in the 1920s, says that this group is finitely generated.

(Notice that I’ve specified points in the rational field ${\mathbb Q}$. If I’d said points in the complex field ${\mathbb C}$, the theorem would not be true - in fact the group $E({\mathbb C})$ is isomorphic to a torus group $S^1 \times S^1$. So the field matters! Most of what I’ll say below is true for any algebraic number field - but I want to keep things simple and only talk about curves over ${\mathbb Q}$.)

So $E({\mathbb Q})$ is a finitely generated abelian group. This means that the group must be isomorphic to

\[ {\mathbb Z}^r \oplus E({\mathbb Q})_{\rm torsion} \]

where the torsion part is a finite group and the number $r$ is called the rank of the group.

Computing the rank of an elliptic curve over a number field (or over ${\mathbb Q}$) turns out to be a hard problem. We need to locate rational points of infinite order, and to figure out the maximum number of such points that are ${\mathbb Z}$-linearly independent. After more than a century of study, there is still no general method for doing this.

Nonetheless, we can compute many examples using special and ad hoc methods. I’ll talk about a database of these in a moment.

Based on a careful study of examples, the Birch-Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture (of Millennium Prize fame) suggests that the rank depends on the relationship of an elliptic curve with the prime numbers.

Reduction modulo prime numbers

Given any curve over ${\mathbb Q}$, we can reduce its equation modulo successive primes $p = 2,3,5,\ldots$ For example, modulo $p = 2$ the equation I wrote down above becomes \[ y^2 + xy + y = x^3 + x^2. \] Over the finite field ${\mathbb F}_2 = {\mathbb Z}/2$, we can count exactly 4 solutions of this curve (including the point at infinity on the $y$-axis). So the group of points over this field has order \[ |E({\mathbb F}_2)| = 4. \] Unlike the rank of the curve over ${\mathbb Q}$, counting the points of an elliptic curve over the prime fields ${\mathbb F}_p$ is easy. For small primes we can just enumerate the solutions as in this example. For larger primes there is an algorithm with complexity $O(p^\frac{1}{4})$.

The key to this counting algorithm (which you can read about in the Wikipedia article) is Hasse’s Theorem, which says that \[ p+1 - 2\sqrt{p} \leq |E({\mathbb F}_p)| \leq p+1 + 2\sqrt{p}. \] So in other words, the number of points $|E({\mathbb F}_p)|$ is ‘close’ to $p$.

It is these counts that are used in the Birch-Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture. I won’t talk about that in this post - though I will make use of the sequence of ‘discrepancies’ \[ a_p = p + 1 - |E({\mathbb F}_p)| \qquad p = 2,3,5,7,\ldots \]

The LMFDB database

With all that as context, where is the data science application?

The authors of [1], followed by those of [2], asked the question: given a large database of elliptic curves of known rank, can one use the methods of machine learning to model the rank directly as a function of the point counts over prime fields?

Incidentally, most known elliptic curves over ${\mathbb Q}$ have rank 0 or 1, with curves of higher rank being much rarer. Could a machine learning model recognise higher rank curves from easily computable features (e.g. the count discrepancies $a_p$)? And could we use it to guide mathematical understanding, perhaps to help prove the Birch-Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture or to generate new insights on the rank?

The data source used in this research is the database LMFDB [3]. This database contains, among other things, around 3.8 million elliptic curves over ${\mathbb Q}$ of known rank up to 5. They are organised by conductor - this is a number whose factorisation encodes primes under which a curve has bad reduction.

In my experiments, I’ve tried to reproduce most of the results of [1]. I’ve used 59,573 elliptic curves (up to isogeny) of rank 0 ,1 or 2 and conductor in the range 1,000-10,000. This is comparable to the experiments in [1] that I’ll talk about, though that paper also does some work with curves of higher conductor which I will ignore.

Murmurations

The paper [1] makes a remarkable observation.

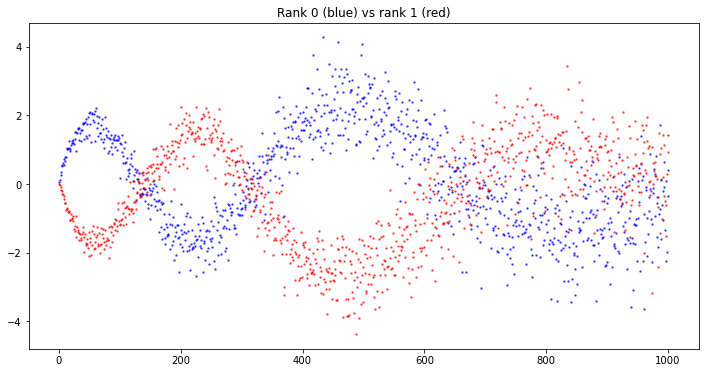

As a preamble, suppose the starting question is ‘can the sequences of $a_p$ counts discriminate curves of different rank?’ If so, then looking directly at examples does not offer much hope:

This plot takes a random curve and shows the sequence $(a_p)$ for the first 1,000 primes. We see that $a_p$ takes values within a range that grows as $O(\sqrt{p})$ in accordance with Hasse’s Theorem. But there is no obvious pattern in the sign of $a_p$, and the picture is indistinguishable to the eye for curves of rank 0,1 or 2.

However, instead of looking at individual curves, [1] looks at the average of $a_p$ over lots of curves (I’ve taken all those with conductor in the range 5,000-10,000 here). Then we see quite a different picture:

These beautiful patterns are the ‘murmurations’ of the title of [1]. Just to be clear: in these plots, each dot represents not an elliptic curve but a prime number. The key observation in [1] and in these plots is that on average there is a very clear signal distinguishing curves of different rank.

(Incidentally, the paper [1] goes on to fit curves to these patterns and tries to understand them. I won’t go there in this post - my interest here is just how to get a predictive model for the rank.)

Predicting the rank

The main claim of [1] is that the rank can reasonably be predicted from a logistic regression model using $(a_p)$ (say for the first 1,000 primes) as feature vector. I have not been able to reproduce this without some further feature engineering (which I suspect is implicit in their work but wasn’t clear to me from the paper).

The problem is that, as in my first plot above, the sequences $(a_p)$ do not themselves exhibit sufficient discriminatory power for the rank. However, the murmuration plot strongly suggests replacing $(a_p)$ by successive window averages: \[ b_p = {\rm average}(a_2, a_3, a_5,\dots, a_p) \] So I have used as feature vector $(b_p)$ for the first 100 primes. I choose 100 based on the clear separation of ranks we see in the murmuration plots for this range. Then the results are impressive.

Projecting these 100-dimensional $b$-vectors (for a sample of 30,000 elliptic curves) to the plane using PCA we get some idea of the discriminatory power:

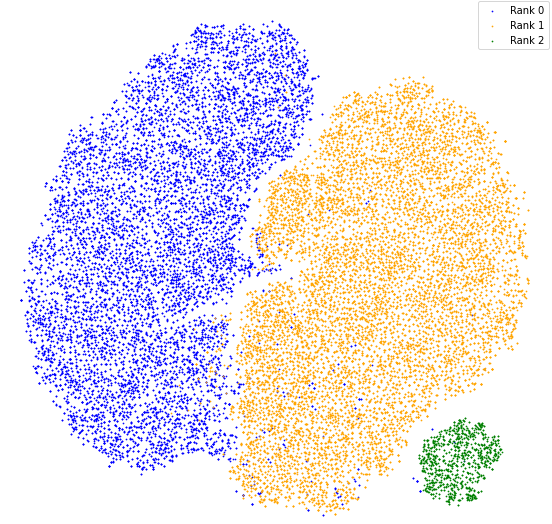

Using t-SNE [4] for a better nonlinear dimensional reduction sharpens the picture (this was the graphic shown at the top of this post):

What this plot shows is that in the 100-dimensional ($b_p$) feature space we’ve chosen, there are very clean decision boundaries separating the three values of the rank. So it’s then a routine matter to train a classifier.

As usual, we’ll partition the data into a training set and a test set, balancing the classes within each. Here are my test results for three models:

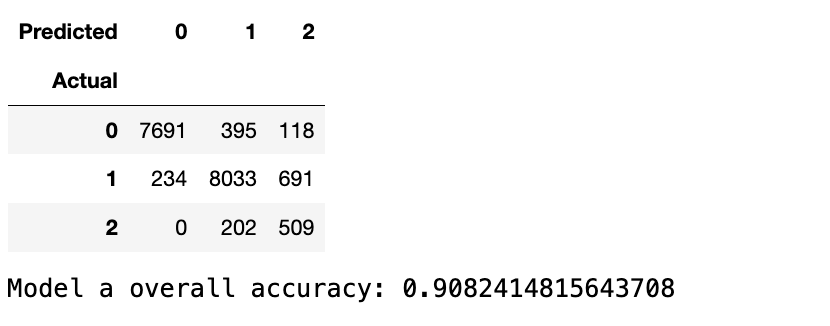

Logistic regression using the $a_p$ features:

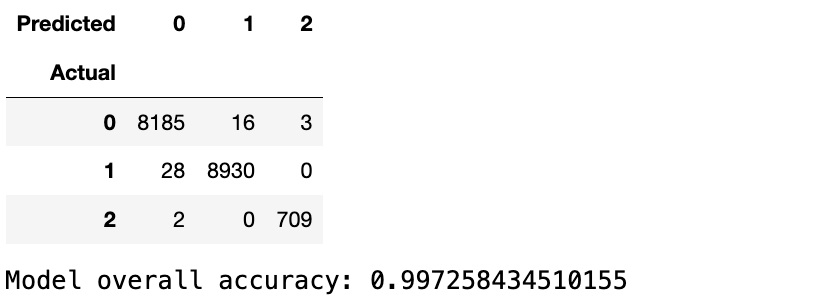

Logistic regression using the $b_p$ features:

Neural network with 2 dense hidden layers using the $b_p$ features:

Jupyter notebooks containing all the code for these experiments (using SageMath and TensorFlow) can be found here.

References

- Yang-Hui He, Kyu-Hwan Lee, Thomas Oliver, Alexey Pozdnyakov: Murmurations of elliptic curves, arXiv.2204.10140 (2022)

- Matija Kazalicki, Domagoj Vlah: Ranks of elliptic curves and deep neural networks, Research in Number Theory 9:53 (2023) or arXiv 2207.06699

- The LMFDB Collaboration, The L-functions and Modular Forms Database (2023)

- Laurens van der Maaten, Geoffrey Hinton: Visualizing Data using t-SNE, Journal of Machine Learning Research 1 (2008).